“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?”

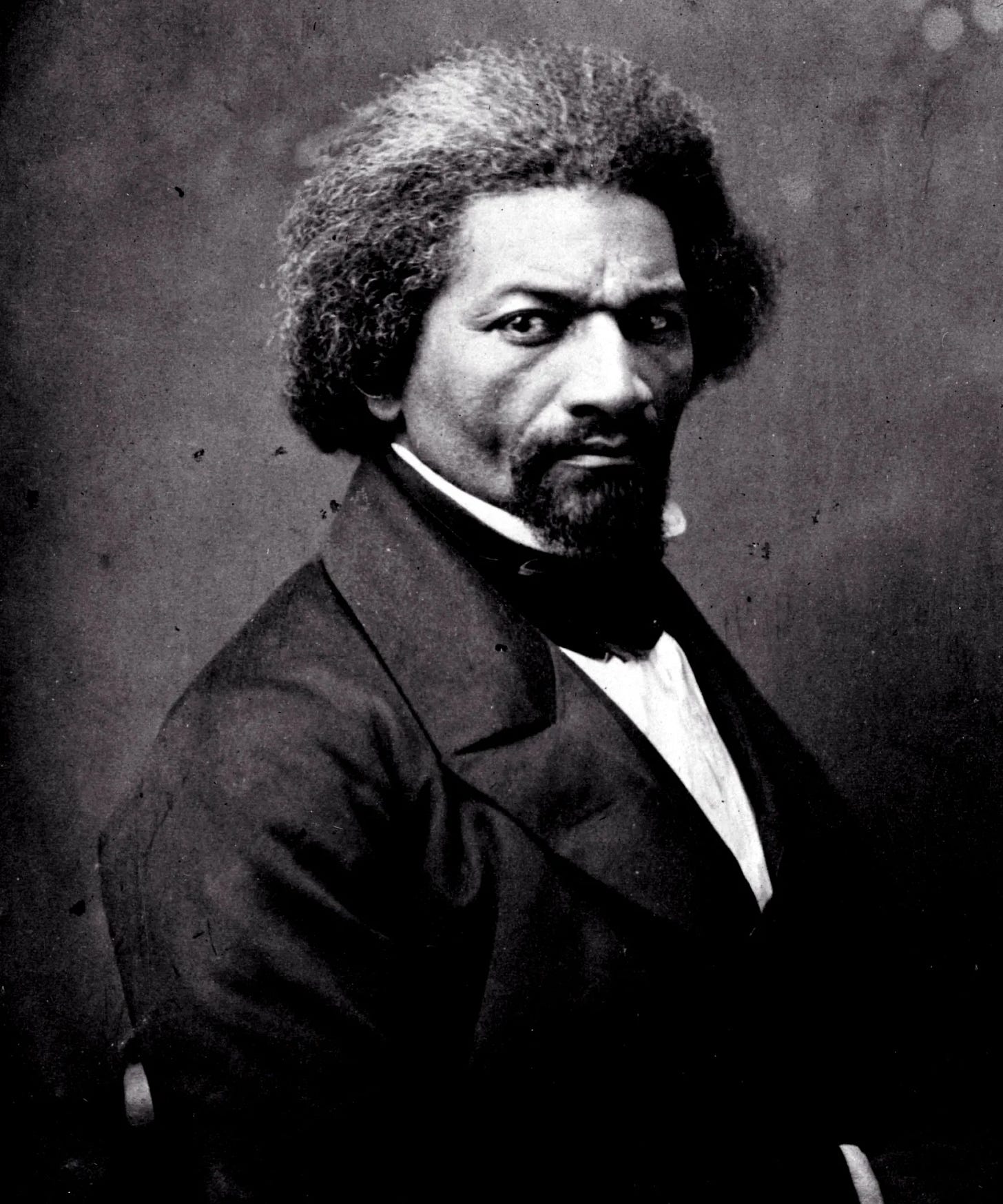

. . . Frederick Douglass famously asked a gathering of the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society on July 5, 1851. It was six years after the escaped slave had published his revealing Narrative of the Life. It was fourteen years before the end of the Civil War and the ultimate proclamation to enslaved peoples in Texas that the Emancipation Proclamation was a reality and they were, in fact, free.

When I taught high school English at a small school just outside Lynchburg, Douglass’s speech was not in the textbook. Excerpts from his Narrative of the Life autobiography were, but I had difficulty connecting the students’ understanding with what Douglass described about slave life.

I turned to the fact of slavery in Lynchburg, and I was stunned by what these young souls did not know: surely such a practice could not have happened in our city! Or perhaps, some students guessed, not wanting to think badly about their hometown, perhaps the slave owners in Lynchburg were kinder, gentler.

What do we do about history that hasn’t been taught? My students in 2022 needed to be asked Douglass’s question, “What to the slave is the Fourth of July?”

“I answer,” Douglass continues about the notion of America’s Independence Day,

“a day that reveals to [the slave], more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; … your national greatness, swelling vanity; … your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery … a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

Three summers ago, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, NPR produced a video in which descendants of Frederick Douglass read excerpts from his speech. I recall my students receiving Douglass’s Narrative words as mere historical artifact, old words that recount curious, if unfortunate, events of a time long gone, and I know that Douglass’s words are still relevant today - crucial even.

As we move toward the Fourth of July, let’s take the time to lament that the words of this speech delivered more than a century and a half ago still speak to ongoing oppression. If we celebrate, let it be over the hope that there is still time to learn and to change, as Douglass’s descendants testify.