Content Warning: This article deals with abuse and suicide. While it does not directly focus on our theme of Education, the Virginia University of Lynchburg plays an important role in the story. The reader can skip this article without missing the arc of our Education theme.

How America tells its story reveals what it believes about truth, justice, and human dignity. On Day 1, Ron Miller stated, “I have long been an advocate of letting history speak for itself. I believe that the whole truth of America’s story must be told, not to stir outrage but to spur us to be better.” The story below follows a life of trauma with devastating consequences. It is what happens when our narratives tell the lie that some of God’s children are less human than others, and it challenges us to stay vigilant as we seek a good and better world.

On Sunday, September 8, 1906, the New York Zoological Gardens, which had opened seven years prior as the largest of its kind in the world, exhibited a human being in a cage. Ota Benga, a member of the peaceful Pygmies1, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was originally taken from his African home, along with eleven others, and put on display at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. The men responsible included the self-centered opportunist Samual P. Verner, who the St. Louis Fair paid to obtain the Congolese, the curator who eagerly put Benga in a monkey cage at the zoo, and the colleagues in their social circles who financed and encouraged them. They were motivated by a sense of racial superiority. This was a time when U.S. Presidents openly agreed with the superiority of the white race2, a time that feels eerily closer in 2025 than it did in the recent past.

Benga endured the trauma of being on display at the Zoological Gardens for twenty days, until an incensed group of Black Christian ministers in New York secured his transfer to an orphanage. One of those ministers, who ran the orphanage, later brought Benga with him to a 1908 convention at the Virginia Theological Seminary in Lynchburg, Virginia. Today known as the Virginia University of Lynchburg, this Historically Black College and University played a significant role in Benga’s life, as it did and still does today in many other lives. (Bridge of Lament will feature Virginia University of Lynchburg in an upcoming article on July 2nd and 3rd.)

Benga’s Lynchburg visit set in motion permanent guardianship with Mary Hayes, the widow of the second president of the seminary, Reverend Gregory Hayes. Benga remained in Lynchburg from 1910 to 1916. In the early years of his time here, Benga experienced joy and delight in this community. He was befriended by a network of teachers and students at the seminary, including Harlem Renaissance poet Anne Spencer. He often played with boys in her neighborhood, including her son Chauncy Spencer. It’s not lost on me that although there were certainly white men and women who supported Benga’s rescue and subsequent care in Lynchburg, it’s largely the Black community who stood in the gap to work on his behalf.

The Substack post “Ota Benga in Lynchburg” by author

provides a beautiful tribute Benga’s life in Lynchburg (as well as a collection of art and poetry inspired by Benga’s story):The kids loved him. He taught them to fish and to hunt, how to make and shoot arrows. How to smoke out a hive and gather the honey, how to recognize which plants and berries out in the woods were safe to eat. How to find their way in the forest. He gave them adventures, nurtured the daring spirit of childhood. It must have stuck: one of the boys he spent time with grew up to become a dashing aviator, a pioneering Tuskeegee airman, whose ten-city tour in a rented biplane paved the way for the program to allow blacks to be trained as pilots for the Army Air Corps as World War II loomed. A part of the community, he mingled with professors and intellectuals and poets, and he learned to read, and these people listened to him and to his story; most of all, though, he was close to the children, until at last it came to the point that he had to explain to the boys one day (after much time playing with them), “I am not a boy, I am a man.” I can’t forever play with you. And once, I had my own children, long ago and in another land, and a wife, and they’re all dead, and then another wife, and she too is gone. Besides, he had adult duties: he did odd jobs at Mammy Joe’s store and worked at the Lynchburg tobacco warehouse - fellow workers remembered how he could get up to the higher racks without a ladder, climbing the poles. With friends of all ages, he’d sing nursery songs and spirituals; outdoors on the heights he’d listen to the women’s choir, their hymns sometimes overtaken by a train’s piercing whistle. He’d drum and dance and chant his own forest songs around fires he and the men and boys built together…

But the trauma of Benga’s exhibition in earlier years and his increasing home sickness haunted him. The racism he brushed against in Lynchburg likely exacerbated this trauma. Pamela Newkirk, Professor of Journalism at New York University, chronicles Benga’s life in her 2015 book, Spectacle. She includes research on trauma, saying, “A study on shame and post-victimization released in 2011 found that individuals who, like Benga, had experienced shame-related trauma risked developing severe psychological symptoms, and also that ‘shame is more likely to be evoked in the individuals, increasing the risk for re-traumatization.”

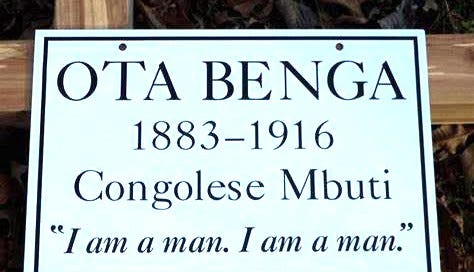

Tragically, in 1916, Benga succumbed to his trauma and homesickness when he took his own life. He is buried next to Gregory Hayes in Lynchburg’s White Rock Cemetery.3

Today, the International Ota Benga Memorial Committee keeps his memory alive4. Founded by artist and activist Ann van de Graaf, the committee’s annual memorial event engages powerful song, dance, and presentation to lament the injustices in Benga’s life and advocate for a broader justice. They are nearing an agreement with the Democratic Republic of the Congo to repatriate Benga’s remains to his home country.

Spurring each other toward the common good includes telling Ota Benga’s story in the pursuit of amends, forgiveness, and a better world. When our U.S. president idolizes a time in our nation that looked more like 1906 than 2006, when Benga’s story has been white-washed or left incomplete, we must let the trauma that Benga endured speak for itself and remind us to seek a more perfect union under a God who desires freedom and life for the African forest dwellers5 in the Democratic Republic of Congo, as much as for us in America.

Kenton Martin, Bridge of Lament project coordinator, is a husband, father, and project manager for a local engineering company. He seeks to follow Jesus into the difficult places of the community.

Ann van de Graaf writes, “He was a Chirichiri, of the Batwa, one of several ethnic groups of small people, collectively called Pygmies. He grew up in the Equatorial Rain Forest with his family. They were nomadic hunter-gatherers, and Ota learned to be a skilled hunter. The Pygmies were at home in the forest and knew its ways. They made huts out of branches, which were bound with vines and then covered with leaves. A peaceable people, they loved to express their reverence for life and the forest through dance. Wild honey was a favorite treat for them; they would climb a tree where a hive was, smoke out the bees, and share the honeycomb.” Ota Benga and the Pygmies: An Ongoing Story, self-published by Ann van de Graff, 2006

Theodore Roosevelt was quoted in the jacket of The Passing Great Race, a “capital book -in purpose, in vision, grasps of the facts our people must need to realize.” The book was written by Madison Grant, the Zoological Society secretary who also cofounded the Bronz Zoo. Pamela Newkirk, in her book Spectacle, The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga, Harper Collins, 2015 states that “the book advocated cleansing America of ‘inferior races’ through birth control, antimiscegenation, racial segregation laws, and mass sterilization.”

Bridge of Lament featured White Rock Cemetery in 2023 with the essay Tending Life in Death and in 2024 with the poem This, Our Passing.

Ann van de Graaf continues in Ota Benga and the Pygmies,

Pygmies are now facing many threats to their survival. In Central Africa the greatest threat is the destruction of the Equatorial Rain Forest, the environment that shelters their nomadic life of hunting and gathering. Over many generations they have intimately learned the life of the forest, which provides them with shelter, food, and medicine. Now, mining companies seeking mineral wealth, along with other multinational developers, are rapidly destroying this life-giving environment.

Displaced Pygmies gravitate to the cities, where they are ill-equipped to survive. In many places they are denied schooling, jobs, and health care. Pygmies generally are treated as second-class citizens in their own countries, and international human rights organizations have even documented cases of cannibalism of Pygmies by the dominant ethnic group.However, some African countries, even with the heavy burden of coping with civil war, genocide, drought, poverty, and disease, have taken steps to improve the lot of the Pygmies within their borders. For example, Burundi's Constitution, adopted in 2005, has guaranteed the Pygmies three seats in the Senate and three seats in the Chamber of Representatives. Rwanda has a Twa senator, and the Cameroon is constructing medical centers and schools in the forests where the Pygmies live.

There have been some efforts by individuals and organizations to help the Pygmies, but only recently have they begun organizing to help themselves. One such organization is the African Congress of Pygmies, based in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Made up of several humanitarian, cultural, and civil rights organizations and entirely run by the Pygmies themselves, the Congress, with very limited funds, helps in the areas of education, economic development, health and welfare, human rights, and cultural activities.It is hoped that through their empowerment, the Pygmies will build on their traditional knowledge and flourish in the technological world of the 21" Century.

Having lived in close harmony with nature, they have much insight and valuable knowledge to share with the rest of the world.