“Knowledge makes a man unfit to be a slave.” -Frederick Douglass

Literacy is central to freedom. In January 1863, news of the Emancipation Proclamation was spread by Union soldiers who read small copies of the proclamation on plantations and in cities across the South. With the end of slavery, states sought to suppress the freedom of black citizens through a series of Jim Crow laws. These laws required literacy tests for voter registration, the maintenance of separate schools segregated by race, the segregation of library facilities, and bans on printing and publishing written matter in favor of social equality or intermarriage.1

Schools and libraries form a bridge of empowerment. In democratic systems, the two institutions assist the populace in making informed decisions about political representation. So it’s worth examining how these two institutional pillars came to be, in America and in Lynchburg.

Boston Latin School is considered the first public school in the country, opening in 1635 for white boys. Two centuries later—in the 1830s—Horace Mann led Massachusetts to establish “common” public schools to teach reading, writing, and arithmetic. In the South, education was private and limited to the wealthy. It wasn’t until 1870 that Virginia’s new constitution established public schools in the state.2

Today we take it for granted that every school has a library where students and teachers can find the books and resources they need. But until the early 1900s, most schools were not built with a dedicated library. In 1903, Mary E. Hall created the first modern American high school library at Girls High School in Brooklyn, New York.3 The rise of libraries for schoolchildren occurred in tandem with the spread of public libraries across the country. Many libraries in the United States started as membership or subscription “clubs,” with membership dues subsidizing the book purchases. In 1833, the first taxpayer-supported library opened in Peterborough, New Hampshire. One of the largest and oldest public libraries is the Boston Public Library, which opened in 1854.4

Following the Civil War, the public library movement took off. The first free public library in Virginia was the Norfolk Public Library, in 1904. Norfolk was a Carnegie library, co-funded by Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie viewed public libraries as a tool for the common man to improve himself through self-education. Under a cost share plan, Carnegie funded construction of library buildings (with his name above the door).5 Carnegie did not require that libraries in the South be integrated, and Norfolk’s public library was segregated for use by white patrons only.

Now we come to the Lynchburg part of the story.

In the late 1800s, George Morgan Jones and his wife donated funds to build a library at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College in memory of two of their daughters. George then had the idea to build a library for the residents of Lynchburg and is said to have started planning. But when George died in 1903, his will specified no funding for a public library. To settle a subsequent lawsuit, his widow Mary Frances Watts Jones donated $50,000 for a public library in George’s memory. The George M. Jones Library Association opened in 1908 at 434 Rivermont Avenue as a privately financed library open to white residents irrespective of gender and religious or sectarian affiliation.

The first librarian at Jones was Roberta Morgan Strother, the wife of William Strother of Strother’s Drugs. Library science at this time was a male field (think Melville Dewey of the Dewey Decimal System). The rationale for hiring Strother was that a woman would be willing to accept lower wages than a man. But the arrangement was short-lived. In 1908 Strother was replaced by William Marshall Black. Black was principal of whites-only E.C. Glass High School; his wife was a great niece of Mary Watts Jones. Black served as Head Librarian from 1908 to 1912 and became the first President of the Virginia Library Association.

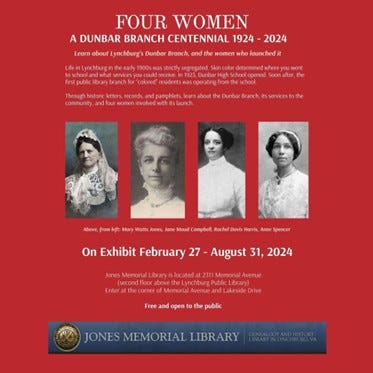

Even though Jones Memorial Library had opened in 1908, it wasn’t until 1924 that African American residents had a public library in Lynchburg. In 1923, Jane Maud Campbell took the helm at Jones as Head Librarian. Campbell had experience at the Newark Public and Boston Public libraries. She quickly established library services to students, black and white, via a weekly lending service (books were transported from the 434 Rivermont building to city schools).

Meanwhile, plans were made to open the first Jones branch in the new “Colored High School” designed by Craighill & Cardwell. This new building, which would be named the Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, included room for a library on the second floor. In an arrangement similar to the Carnegie model, the city School Board provided the room, bookshelves, heat, light and janitor’s services. Jones Memorial Library provided the books, furniture, and library staff.6

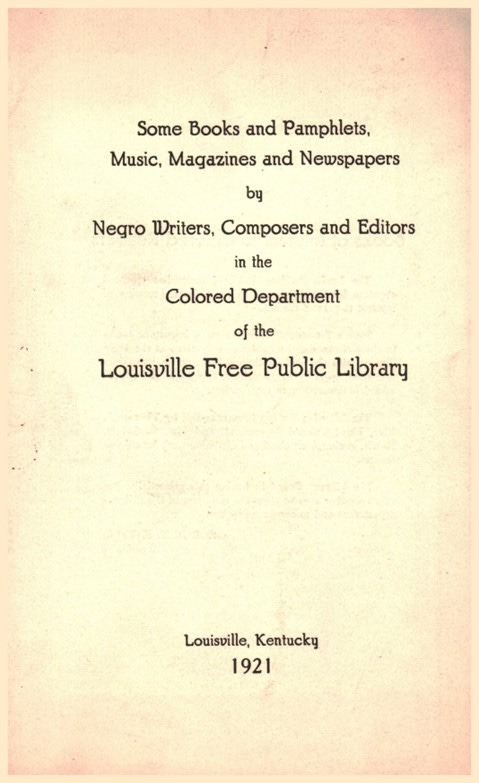

In December 1923, Campbell arranged for Rachel Davis Harris to travel from Louisville, Kentucky, to open the Dunbar library and hire a permanent librarian. As an African American librarian frequently called to consult across the South, Harris was already familiar with the region. In 1921 she had trained Ella F. Bowden and opened the Gainsboro Branch in Roanoke – the first public library branch in Virginia to offer segregated services to blacks. In 1923-24, Harris was on contract to Jones from her usual duties at Louisville Free Public Library’s Western Colored Branch (the first American public library built for and staffed by African Americans).7 Harris spent several weeks in Lynchburg and likely stayed at the home of Anne and Edward Spencer. Anne Spencer, a published poet, was selected as Dunbar Branch librarian, serving in that capacity from 1924 until 1947.

While the Dunbar library served students and teachers during the school day, at night it was open to residents. In this way, Dunbar doubled as a public library “branch” for African American residents. However, when schools were closed during the summer there was no public library open to the black community, a disservice that continued until the Lynchburg Public Library opened in 1966. The Dunbar library is referred in Jones documents as the “Dunbar Branch” because it operated under Jones funding and management until 1947.

In the 1930s and 40s, the civil rights movement was gaining momentum. Clarence William Seay served as Dunbar’s first black principal, and there was increasing advocacy for a taxpayer-funded racially integrated library. Meanwhile, Campbell and Spencer were ready to retire, and Jones was feeling the financial effects of the great depression and World War II. In 1947, Jones consolidated all of its library services back to 434 Rivermont Avenue and turned its school “branches” over to the School Board. The City manager’s office was prodded to look into whether to build a taxpayer supported, integrated public library. They didn’t get far.

Integrated libraries began to open across the state (Richmond and Norfolk in 1947, Alexandria in 1950, Winchester in 1953, Danville & Petersburg in 1960). It wasn’t until 1966–more than 40 years after the Dunbar branch opened–that Lynchburg finally had an integrated public library. Throughout that time, black residents were denied use of the 434 Rivermont Avenue library and continued to use the Dunbar High School Library. Black residents also used a reading library at the Peaceful Baptists Religious Education and Social Center, at the corner of 13th and Fillmore Streets.

Given the alignment of the public school and public library movements, you might think that integration of public schools and public libraries in Virginia would be closely aligned. Virginia’s public libraries were by and large much quicker at integrating than her schools. The integration of knowledge institutions in Virginia also followed an “either/or” pattern. Cities tended to display a split approach to the integration of libraries and schools.

While Richmond’s library integrated in 1947, it wasn’t until 1970 that the city’s schools integrated. Norfolk’s library also integrated in 1947 and the Charlottesville library integrated in 1948; both school systems only integrated in 1959. Alexandria integrated some public library services in 1959, but the school system didn’t integrate until 1964. Winchester’s library integrated in 1953; its schools integrated in 1966. Lynchburg and Petersburg each integrated their libraries later. Petersburg Public Library integrated in 1960; Lynchburg Public Library opened as an integrated public library in 1966 while Jones Memorial Library integrated in 1969. In both cities, integration of the libraries preceded the school systems (1963 in Petersburg; 1970 in Lynchburg).

Libraries and schools are partners in literacy. Public libraries are a bridge to knowledge. But it is lamentable that in Virginia and across the South, when a public library integrated, there was continued delay of school integration for years, or decades, afterwards. In this sense, libraries served both as a door to opportunity and a speedbump towards fuller freedom.

In 2024, Jones Memorial Library commemorated the centennial anniversary of the opening of the Dunbar Branch library. Titled “Four Women,” the exhibit shared the impact of four librarians and the road to racial integration of the city’s libraries. The exhibit panels are currently on loan to Dunbar Middle School. Readers are invited to visit the digital exhibit at this link.

Deborah Smith is Executive Director of the Jones Memorial Library in Lynchburg, Virginia. She holds an M.L.I.S. from Kent State University. Deb's career includes 20+ years in records management, libraries, and archives. She is a frequent presenter and writes about issues related to women, linguistic minorities, and enslaved persons in archival collections.

“Examples of Jim Crow Laws. Oct. 1960-Civil Rights.” Jim Crow Museum. URL https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/links/misclink/examples.htm. URL retrieved February 25, 2025

Encyclopedia Virginia. “The Establishment of the Public School System in Virginia.” URL https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/public-school-system-in-virginia-establishment-of-the/#:~:text=The%20first%20statewide%20system%20of,and%20enduring%20accomplishments%20of%20Reconstruction. URL retrieved February 25, 2025.

Alto, Teresa. “Mary E. Hall: Dawn of the Professional School Librarian.” School Library Monthly 29(1). Sept-Oct 2012. URL https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ980030. URL retrieved February 25, 2025.

“A History of US Public Libraries: First Public Libraries”. Digital Public Library of America. Exhibitions. URL https://dp.la/exhibitions/history-us-public-libraries/beginnings/first-public-libraries URL retrieved February 25, 2025.

“A History of US Public Libraries: Funding Carnegie Libraries”. Digital Public Library of America. Exhibitions. UR https://dp.la/exhibitions/history-us-public-libraries/carnegie-libraries/funding-carnegie-libraries. URL retrieved February 25, 2025.

Jones Memorial Library. “Letters to Louisville.” Four Women: A Dunbar Branch Centennial exhibit. URL https://digitaljones.omeka.net/exhibits/show/four-women--dunbar-branch/letters-to-louisville. URL retrieved February 25, 2025.

It’s not clear which American library was the first to integrate racially. The Franklin Public Library in Franklin, Massachusetts was open to ‘all residents’ in 1790. The Philadelphia Library of Colored Persons was co-founded in 1833; use of the library required a paid membership. The public building that housed the Washington (D.C.) Public Library was racially integrated in 1903; the Navesink, New Jersey library allowed blacks and whites to use the library at the same time in 1947. Following a 1939 sit-in, the Alexandra, VA public library was the first library to integrate in the South, by phasing in access first for students and then for adults in 1959 and then integrating for children in 1962.