Day 10: The Placement of Lynchburg's Confederate Monument

In addition to examining the monument’s historical context, we should consider the significance of its physical placement.

Yesterday, we examined our Confederate monument’s historical context. We saw that it was put up by a white crowd well aware that they’d just ousted the city’s Black councilmembers, and their representatives were already rewriting the state constitution to keep Black Virginians from voting for another 65 years. We saw that they stuffed the monument with testimonials to their view that white rule and Black subjugation were the right way to structure society.

But in addition to examining the monument’s historical context, we should examine its positional context. That is, quite literally, we should look at where it has been placed in relation to the things around it.

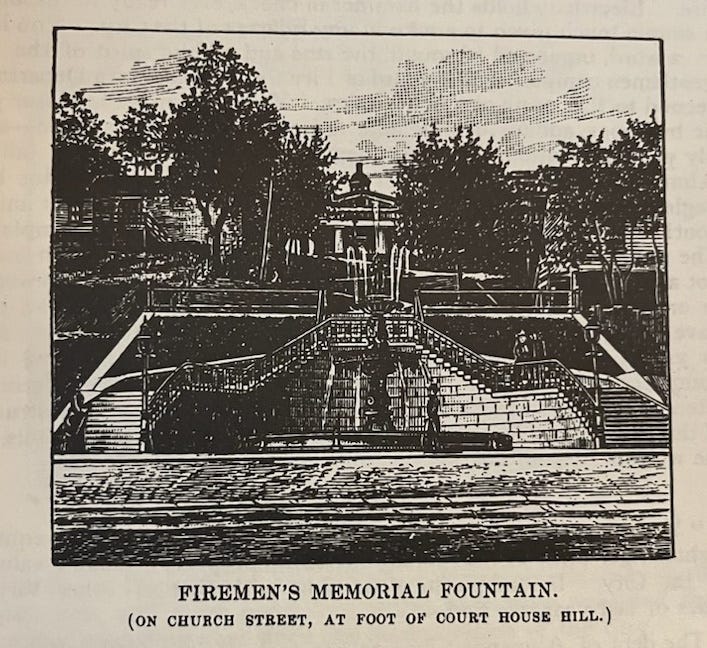

At present, the Confederate monument sits at the top of Monument Terrace. In that context, it may be easy to mistake the Confederate monument as just another war memorial and nothing more. But in 1900, there was no Monument Terrace. There was a fountain honoring firefighters who had lost their lives battling a tragic 1883 fire at the bottom of the hill, and there was the court house at the top of the hill.

When the Confederate monument was placed in 1900, it was placed in front of the Lynchburg Courthouse.

This is loaded with meaning. At the turn of the century, cities all across the South were placing Confederate memorials in front of courthouses as pointed and aggressive messaging. They were saying, as loudly as they could: in these halls, white justice rules. They were restating what the vice president of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens, had famously said to loud applause:

“All of the white race, however high or low, rich or poor, are equal in the eye of the law. Not so with the negro. Subordination is his place. …[B]y experience we know that it is best, not only for the superior, but for the inferior race, that it should be so. It is, indeed, in conformity with the ordinance of the Creator.”1

This white supremacist view had not changed in the 39 years from Stephens’ speech (1861) to the placement of Lynchburg’s Confederate monument (1900). When white Lynchburgers put up a memorial to the Confederacy and emotionally insisted that its cause was holy and right and must be propagated to Southern children, this is precisely what they meant: “the white race” is equally protected by the law, but subordination is God’s will for Black people.

And what better way to symbolize that view for White citizens, and assert it over Black citizens, than to put a memorial to white supremacy directly in front of the city’s halls of justice.

Journalist and historian Isabel Wilkerson writes about the effect that placing Confederate monuments in front of courthouses had on Black men and women:

“People still raw from the trauma of floggings and family rupture, and the descendants of those people, were now forced to live amid monuments to the men who had gone to war to keep them at the level of livestock. To enter a courthouse to stand trial in a case that they were all but certain to lose, survivors of slavery had to pass statues of Confederate soldiers looking down from literal pedestals.”2

Similarly, Lecia Brooks, Chief of Staff at the Southern Poverty Center, has also written about the fully intended effect of this placement. FiveThirtyEight summarizes its interview with her:

“[P]lacing these memorials on courthouse property … was meant to remind Black Americans of the struggle and subjugation they would face in their fight for civil rights and equal protection under the law. Black Americans have long understood the symbolism of those monuments. ‘I know what this statue means,’ said Brooks. ‘It's a reminder to stay in my place.’”

The director of the Lynchburg Museum, Ted Delaney, also recognizes the significance of the monument’s placement:

“I have heard the people say it’s even more complicated … because the courts and the police department are located literally across the streets. And so by placing the monument near those spaces, you complicate it in another way.”

These comments help us bring the issue into the present. The Confederate memorial is not just a historical problem. It most certainly is a historical problem—a problem of how we remember the past and what we choose as a city to publicly honor. But it is also a present and human problem.

It’s a problem of equal justice.

The old courthouse is now a museum, but the new courthouse is also within the sightline of this monument that was originally placed there precisely to say, “in this town, justice is white.” Every defendant enters the courthouse under the gaze of a statue erected upon these words—not just metaphorically, but literally in the base of the statue:

“Reason, common sense, true humanity to the black, as well as the safety of the white race, required that the inferior race should be kept in a state of subordination.”

And

“The Nation’s Ward, a N****r”

Conclusion

Friends, this is a travesty.

I understand and respect the view expressed by some, including some on Lynchburg’s African American Cultural Committee, that the city has bigger issues to deal with in terms of racial justice, that a merely symbolic change does less good for our community than addressing practical realities like food, housing, employment, and safety.

I respect that view, and certainly we must address those issues, but here is the thought I keep coming back to:

There is no reconciliation without repentance, and no one can repent something while celebrating it.

Lynchburg’s Confederate memorial is a monument to white supremacy. That is clear from the historical context of the statue, the words chosen to represent it, and the position it was placed in. Frederick Douglass in 1870 correctly foresaw how the future would regard monuments to the Confederacy:

“The future will look to history, and by its lessons will be formed opinions of the merits of the great butchery inaugurated by politicians in behalf of slavery and against free government. …Every monument built in memory of the Confederacy… will prove monuments of folly, both in the memories of a wicked rebellion which they must necessarily perpetuate, and in the failure to accomplish the particular purpose had in view by those who build them. It is a needless record of stupidity and wrong.”3

The theme of our project is building a bridge from lament over the history of white supremacy in our city, to joy in the Beloved Community that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. envisioned. It is a Beloved Community offered to us by the scripture readings that our white ancestors ignored that Divine Mercy morning in April 1900: how blessed it is to be “of one heart and soul” and hold our city in common—to see it as a space where all are equally welcome, equally respected, and equally protected by our laws. How good and pleasant it is when brothers and sisters dwell together in unity.

I submit that we cannot attain that vision and keep a symbol of white supremacy in a place of public honor and civic authority.

Given the context around Lynchburg’s Confederate monument—what it celebrates, what it meant to the people who erected it, what words and ideas it literally stands upon—it must be removed or relocated into the adjacent museum where its history can be fully told, without its cause being celebrated.

And as for what to put in its place, I note that our city has no statue honoring its founder, John Lynch. The local historian Rebecca Pickard is doing fantastic research about the abolitionism of John Lynch, his sister Sarah Lynch Terrell, and the Lynchburg Quakers. A statue to John Lynch and his legacy seems most fitting for our city’s place of highest honor—facing the historic courthouse and at the top of Monument Terrace.

Alexander Stephens, “Cornerstone Speech,” March 21, 1861. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/cornerstone-speech

Isabel Wilkerson, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. Random House, 2020.

Frederick Douglass, editor, The New National Era, December 1, 1870. Emphasis added.

I stopped in Winchester, VA this summer and saw a confederate statue in front of their old courthouse too. This article connects the dots.

Also, for more thoughtful reading on statues and history Diana Bass’s recent https://open.substack.com/pub/dianabutlerbass/p/on-statues-history-politics-and-division?r=re0nu&utm_medium=ios