It would be impossible to write about race and education in Lynchburg without mentioning Liberty University. Lynchburg is ostensibly a “college town,” with the Virginia University of Lynchburg (1886), Randolph College (1891), University of Lynchburg (1903), Centra College, a nursing and healthcare institution (1912), and Central Virginia Community College (1966) within the city limits, in addition to Liberty (1971). Some would also include Sweet Briar College (1901), the women’s college in nearby Amherst, since it’s only thirteen miles away.

That said, Liberty University has had a greater economic footprint in Lynchburg than any of the others. Liberty is the largest employer in the Lynchburg Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), with over $500 million in direct spending annually by the university, its students, and visitors, generating more than $1 billion in total economic activity. This doesn’t include the 450,000 hours of volunteer service provided by Liberty students each year, with an estimated value of $5.1 million. These numbers are significant, but shouldn’t be a surprise - Liberty University’s total enrollment, including online students, is larger than the City of Lynchburg’s population and nearly half the size of the Lynchburg MSA, which includes the city and the counties of Amherst, Appomattox, Bedford, and Campbell.

However, Liberty’s cultural impact on Lynchburg has been equally profound. The university has been a hub of conservative evangelical political activism for most of its existence. It is probably best known nationally through the Moral Majority, a conservative Christian organization established by Liberty University's founder, the Rev. Jerry Falwell, Sr., and other evangelical leaders in 1979. While Liberty University’s presence has brought national attention to Lynchburg through major concerts, conferences, athletics, and other cultural events, it has also brought the political spotlight on the city in ways Lynchburg hasn’t always welcomed.

While most Lynchburg residents understand and appreciate Liberty’s economic impact on the city, others have criticized its political entanglements and their impact on the city’s image. They believe the city’s diversity and secular traditions are overshadowed by the conservative brand of Christianity fostered by Liberty.

One commenter in Reddit’s r/Lynchburg forum put it succinctly:

“There’s a cultural divide. Liberty students live in a bubble, and sometimes it’s like there are two Lynchburgs.”

I have observed these “two Lynchburgs” firsthand. I served as an associate dean, interim dean, and online dean, as well as an assistant professor, at Liberty University from August 2011 to September 2022. I have also been actively involved in the Lynchburg community through my home church, Mosaic Church, located in The Plaza near E.C. Glass High School, the No Walls Ministry, dedicated to removing cultural and denominational barriers between Christians and churches in the interest of serving the community, and FIVE18 Family Services, which exists to help central Virginia families in need with care, counseling, and community resources.

Through my church and nonprofit work, I’ve seen a side of life in Lynchburg that has profoundly changed me and given me a different perspective from the conservative Christian worldview I had embraced for the better part of my adult life, which was partly responsible for my hiring at Liberty University.

Part of that perspective included Liberty University’s impact on Black residents and students. I was afforded a unique view into the lives of Black students at Liberty, as I was, to my knowledge, the only Black dean at any level during my time there. This meant that Black students were not only aware of me but also felt comfortable enough to speak candidly with me about their experiences. I also participated in the Center for Multicultural Enrichment, which provided a gathering place and culturally relevant programs for non-white students and invited white students to enrich their campus experience through exposure to people and experiences they hadn’t encountered before. For reasons I’m unsure of, this center was eventually closed, and nothing quite like it has taken its place.

Since Liberty University was founded in 1971, by which time school integration was the law of the land and increasingly being enforced, it wasn’t a major player in the battles of the 1960s civil rights movement. However, Jerry Falwell, Sr., who in 1956 founded Thomas Road Baptist Church (TRBC) and launched the Old Time Gospel Hour, a nationally syndicated television and radio ministry, had a great deal to say about the civil rights movement and the push toward equal rights for Black Americans. Before the civil rights movement, evangelical pastors had largely avoided the political arena, with the theological rationale that the spiritual mission of the church and the secular world of politics were incompatible. Politics was viewed as a distraction from soul-winning and personal salvation.

However, Falwell was an early adopter of political engagement on behalf of conservative evangelicalism. While the movement is probably best known today for its opposition to abortion, feminism, and LGBTQ+ rights and its promulgation of social conservative values, it didn’t start that way.

In 1979, The late Paul Weyrich, a right-wing Catholic and political operative, sought to organize evangelical pastors to oppose increasing liberalism in American society:

“Weyrich hoped to produce a well-funded evangelical lobbying outfit that could lend grassroots muscle to the top-heavy Republican Party and effectively mobilize the vanquished forces of massive resistance into a new political bloc. In discussions with Falwell, Weyrich cited various social ills that necessitated evangelical involvement in politics, particularly abortion, school prayer and the rise of feminism. His pleas initially fell on deaf ears.

‘I was trying to get those people interested in those issues and I utterly failed,’ Weyrich recalled in an interview in the early 1990s.”1

Falwell had other things on his mind. Since the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, he perceived racial integration as the greatest threat to American stability. In 1958, he gave a sermon at Thomas Road Baptist Church entitled, “Segregation or Integration: Which?”

“If Chief Justice Warren and his associates had known God's word and had desired to do the Lord's will, I am quite confident that the 1954 decision would never have been made. The facilities should be separate. When God has drawn a line of distinction, we should not attempt to cross that line.

“The true Negro does not want integration...He realizes his potential is far better among his own race.”2

Falwell warned that integration “will destroy our race eventually” and spoke ominously of interracial marriages, declaring, “In one northern city, a pastor friend of mine tells me that a couple of opposite race live next door to his church as man and wife.”

In a 1964 sermon, “Ministers and Marchers,” Falwell accused the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., of being a Communist subversive, declaring that he and other civil rights leaders were “known to have left-wing associations,” and were being exploited by Communists who were “taking advantage of a tense situation in our land, and are exploiting every incident to bring about violence and bloodshed.” Falwell even supported notorious FBI director J. Edgar Hoover in his attempts to discredit King by distributing FBI-manufactured propaganda portraying King as a tool of the Communists.

Later, when Falwell tried to retrieve all copies of his sermons from before 1970, this particular one, which had been distributed as a pamphlet after his presentation, remained accessible. In 1980, he retracted this sermon, describing it as a “false prophecy.”

Ironically, it was in that same sermon that Falwell concluded, “Preachers are not called to be politicians, but soul winners.” While he meant it as a rebuke of Dr. King’s political activism, it reflects on him as one of the founding fathers of the Christian Right, which remains a potent political force to this day.

Falwell’s opposition to racial integration extended beyond the pulpit. He was actively involved as the chaplain of the Lynchburg chapter of the Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberty. This state organization supported “Massive Resistance” —a movement spearheaded by U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. of Virginia, aimed at defending segregation and resisting federal intervention in state politics.

Over time, massive resistance began to crumble as federal and state courts ruled that the tactic of closing schools rather than integrating them was unconstitutional. Nevertheless, integration was slow in coming to Lynchburg. Public schools weren’t fully integrated until 1970, 16 years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision. As for the local colleges, while Virginia University of Lynchburg is an HBCU (Historically Black College or University) and has served Black students since its founding, other colleges took a decade or more after Brown to integrate. The University of Lynchburg, then known as Lynchburg College, didn’t integrate until 1964, and Randolph College admitted its first Black student in 1966.

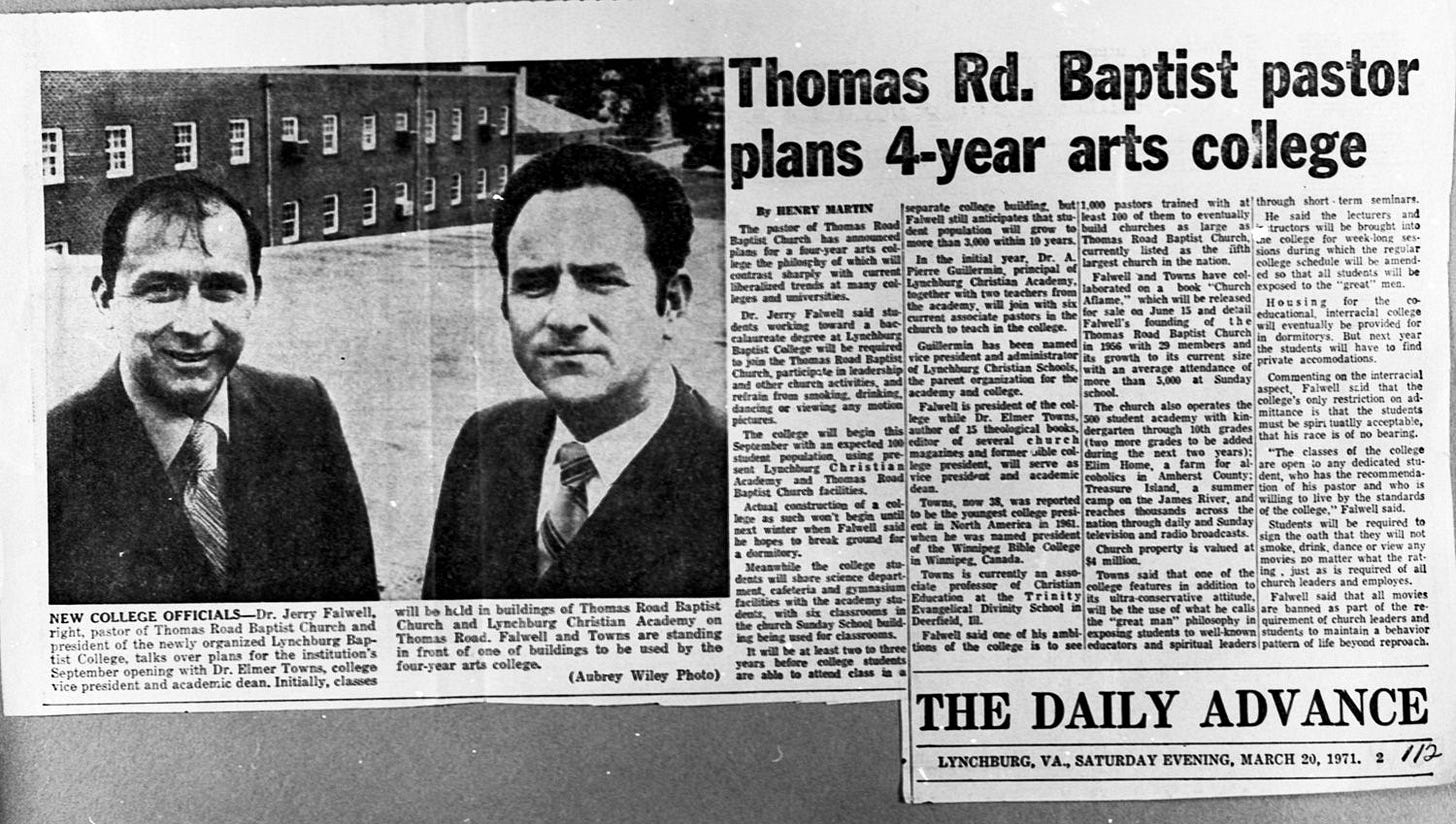

As integration took hold in public schools, Falwell established the Lynchburg Christian Academy in 1967, which later became Liberty Christian Academy (LCA). While there was no explicit policy against Black students attending LCA, the only students admitted during the first two years were white students, and the Lynchburg News and Advance, in a November 10, 1966, article announcing the creation of the school, referred to it as “a private school for white students.” The Brown ruling did not apply to private schools, and “segregation academies” sprang up across the South, prompting white flight from newly integrated public schools.

While Paul Weyrich attempted and initially failed to mobilize evangelical pastors over cultural issues he thought would be important to them, he learned that another form of government “overreach” was enough to get them to engage politically.

“For Falwell and his allies, the true impetus for political action came when the Supreme Court ruled in Green v. Connally to revoke the tax-exempt status of racially discriminatory private schools in 1971. At about the same time, the Internal Revenue Service moved to revoke the tax-exempt status of Bob Jones University, which forbade interracial dating (Blacks were denied entry until 1971). Falwell was furious, complaining, ‘In some states it's easier to open a massage parlor than to open a Christian school.’”3

Weyrich later said, “What changed their mind was Jimmy Carter's intervention against the Christian schools, trying to deny them tax-exempt status on the basis of so-called de facto segregation.” A former associate of Falwell and the Moral Majority also recalls the threat to segregated Christian schools as a galvanizing force for this political movement:

“But were it not for the federal government's attempts to enable little black boys and black girls to go to school with little white boys and white girls, the Christian right's culture war would likely never have come into being. ‘The Religious New Right did not start because of a concern about abortion,’ former Falwell ally Ed Dobson told author Randall Balmer in 1990. ‘I sat in the non-smoke-filled back room with the Moral Majority, and I frankly do not remember abortion ever being mentioned as a reason why we ought to do something.’”4

It was the threat of forced integration of whites-only Christian schools, not abortion, feminism, or LGBTQ rights, that birthed the Moral Majority. However, the seeds of a conversion in Rev. Falwell’s views on racial integration were planted when he invited Dr. Pierre Guillermin to assume the role of administrator for LCA, which he accepted on the condition that Falwell would also seek to establish a Christian university in Lynchburg.

In 1971, Falwell founded Lynchburg Baptist College, which was renamed Liberty Baptist College in 1975 and Liberty University in 1985. They admitted one Black student in their first year. However, by the time the college was established, Falwell had begun to moderate his views on race, a change of heart his associate and Liberty co-founder, Dr. Elmer Towns, attributed in part to a bus ministry started by TRBC in 1968. These buses would provide transportation for children and families who had no means of getting to church services on Sunday mornings. Increasingly, Black children and families began attending TRBC and wanted to become members, and the predominantly white church slowly began to integrate.

According to Dr. Towns, in 1979, Rev. Falwell attended a service at Court Street Baptist Church, the oldest African American church in Lynchburg, where the Rev. Jesse Jackson, a renowned civil rights activist who had served with Dr. King and was with him when he was assassinated, was scheduled to speak. Falwell spoke with Rev. Jackson beforehand and asked for a few minutes to address the congregation, offering Jackson the opportunity to speak to the congregation at TRBC the following Sunday. According to Dr. Towns, Falwell apologized for his prior beliefs and statements on race:

“According to Towns, Falwell admitted that his beliefs had been wrong. He said, ‘I’m sorry—I was wrong. I was prejudiced. I’m a product of Campbell County here. I believed what I was always told, but I was wrong.’ Falwell then extended a scholarship to any person in the building who wanted to attend LU. Towns quoted Falwell as saying, ‘It’s easy to say, ‘I’m sorry,’ but if you can say it with money, it means more.’ Additionally, in 1980, Falwell took Lynchburg African American civil rights advocate M.W. Thornhill, Jr., to lunch to apologize for his past actions, among other public apologies he gave.”5

Jackson eventually spoke at TRBC in 1985, and although he and Falwell had significant ideological differences and engaged in spirited public debates in the years that followed, they developed a mutual respect for each other. They were committed to maintaining civil discourse regardless of the intensity of their beliefs. After Rev. Falwell’s sudden death in 2007, Jackson noted:

“Over the years we became friends; sometimes we had polar opposite points of view.… I have many fond memories of him. He leaves a great legacy of service and a great university behind. He’s left his footprints in the sands of time.”6

In 2007, the Black residential student population at Liberty was about 10% of the student body, which was modest compared to the Black population in Lynchburg, which comprised 29.7% of the city’s total population, or the Black population in the state of Virginia, which was about 20% of the total. This isn’t completely surprising due to the dichotomy between the political alignments of conservative evangelical Christians and most Black Americans, but it was a favorable reflection of Falwell’s changed heart on the topic of integration. I often heard anecdotes of him handing out LU scholarships to needy young people while going about his daily business, forcing his staff to scramble to satisfy the commitments he made, and several of the beneficiaries of his generosity were Black.

His repentance for his past prejudices and embrace of Black Americans as not only equal in the sight of Christ but also under the law is a fitting coda to the life of a public pastor who, like so many Southern white men of his era, was forced to confront the sin of racism and choose between the culture and the way of Christ. Not everyone found their way to the Cross, and the darkness in their hearts was transmitted to future generations.

Ten years ago, on June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof, a white man hoping to trigger a “race war,” walked into a Wednesday evening Bible study at Emmanuel AME Church, a predominantly Black church in Charleston, South Carolina and the oldest Black church in the South, and murdered nine people, including the senior pastor, and injured one. This shocking crime prompted a national debate on race relations and the persistence of Confederate iconography, and among the voices who spoke out against the culture of racism in the South was Jonathan Falwell, the son of the late pastor and his successor as the senior pastor at TRBC. In a sermon to his congregation and their national TV and radio audience on July 19, 2015, he said:

“We as Americans, we have one flag to fly. That’s the American flag, and we should not be flying a flag that is a stumbling block that is hurtful to other people in our midst, in our country and in our church. We shouldn’t be doing it…It maddens me, it embarrasses me that in our country today in 2015, some 50-odd years later from the 1960s, that we are still dealing with racism.”7

As he finished his sermon, he spoke of the need for “genuine repentance…It means to recognize that what I did was wrong, and I am going to do my level best to not do it again.” One wonders if he wasn’t thinking of his father when he made that statement.

Next: Liberty’s struggle with race in the Obama era, the appointment of its first chief diversity officer, and its actions in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

Ron Miller is a college administrator, educator, church elder, community activist, veteran, and computer nerd. He lives in Forest, Virginia, with his family. A devoted husband and father of three adult children, he is soon to be a proud grandfather.

Blumenthal, Max. “Agent of Intolerance.” The Nation, 16 May, 2007, www.thenation.com/article/archive/agent-intolerance/tnamp/

Blumenthal, Max. “Agent of Intolerance.” The Nation, 16 May, 2007, www.thenation.com/article/archive/agent-intolerance/tnamp/

Blumenthal, Max. “Agent of Intolerance.” The Nation, 16 May, 2007, www.thenation.com/article/archive/agent-intolerance/tnamp/

Blumenthal, Max. “Agent of Intolerance.” The Nation, 16 May, 2007, www.thenation.com/article/archive/agent-intolerance/tnamp/

Legg, Kathryn, "Equal in His Sight: An Examination of the Evolving Opinions on Race in the Life of Jerry Falwell, Sr." (2019). Senior Honors Theses. 928.

https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/honors/928

This is good. Thank you. Looking forward to reading more.