Day 14: Rest from Lament - Tending Gardens

Poet Anne Spencer offers a vision for ways to inspire hope and seek change

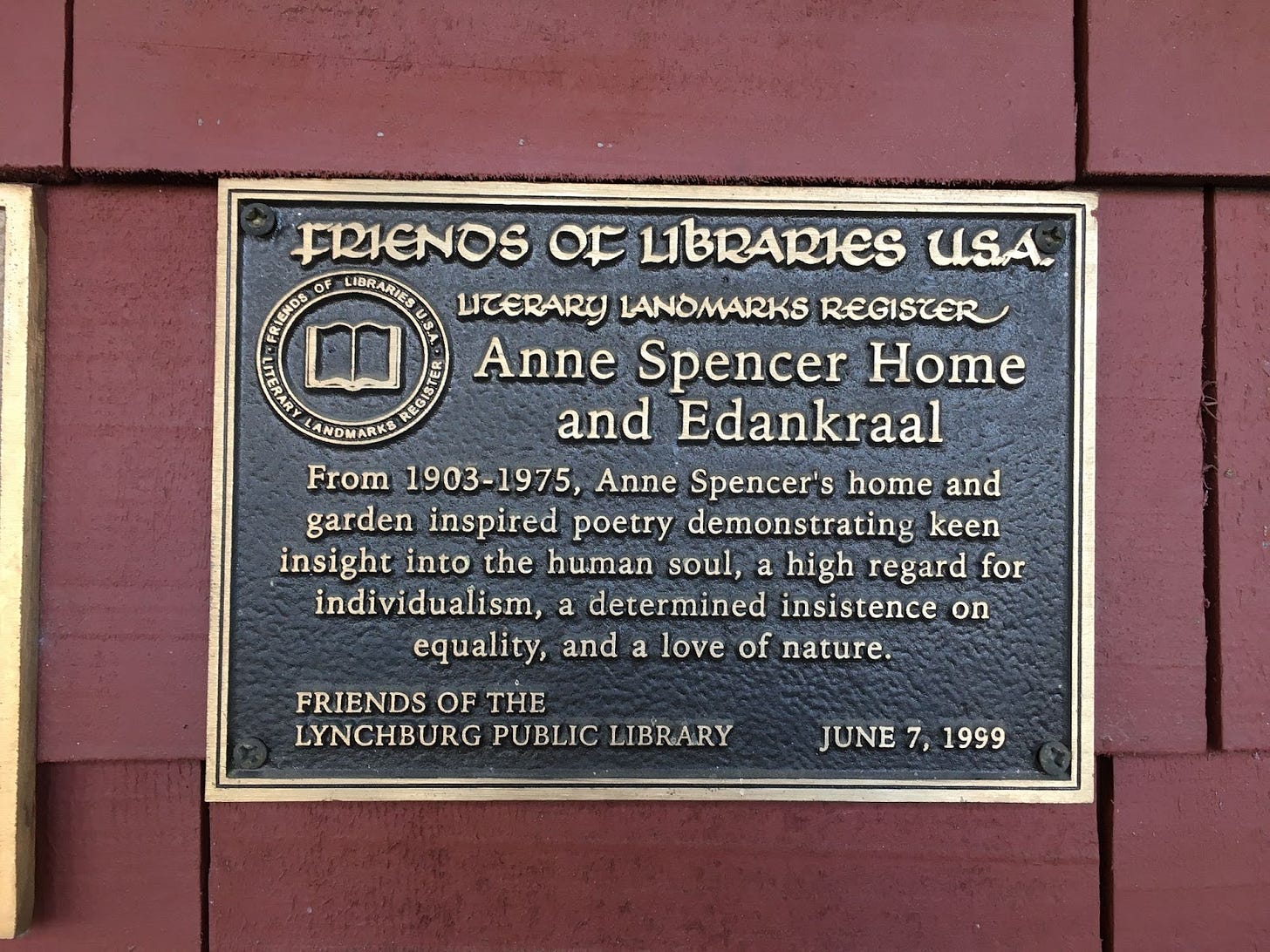

Lynchburg, Virginia, has a poetic claim to fame.

Harlem Renaissance poet Anne Spencer was born Annie Bethel Bannister, the daughter of former slaves, in 1882 in Henry County, and she was destined for not only great work, but also local beauty.

Across her adult life, Spencer hosted the likes of Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Martin Luther King, Jr., in the sitting room of her Pierce Street home. In 1918, with the help of James Weldon Johnson, she assisted in reestablishing the Lynchburg chapter of the NAACP. She wrote notable poems that addressed the ongoing reality of racism across eras, from the Harlem Renaissance to the Civil Rights movement, and in 1973, she became the first African American woman to be featured in the Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry.

But her activities and community involvement ranged even more broadly. At work, Spencer tended the Black youth of Lynchburg as librarian at the segregated Paul Laurence Dunbar High School (now Dunbar Middle). At home, she tended her sprawling backyard city garden, lush and green and filled with life.

And she wrote poetry about growing things, often from Edankraal: the tiny writing house her beloved husband, Edward, constructed for her amid the gardens behind their house. In these varied pursuits, Spencer offers an expansive vision for ways to inspire hope and seek change.

Yes, in some instances, she wrote searing poems about race and history, like “White Things,” which begins:

Most things are colorful things-

-the sky, earth, and sea.

Black men are most men;

but the white are free!

. . . and culminates in an indictment of the white enslavers, who “pyred a race of black, black men” on this continent, and yet demanded that God, the “Man-maker, make white!”1

But Spencer is most known for her poems about gardens. Her lines are rife with earth clods and grapes, nasturtiums and curly worms. She enverses her own “garden at dusk” as “the soul of love”2 and thanks the earth “for the pleasure of [its] language.”3

Why would a woman who ran in circles with Hughes, who had the ear of MLK and the support of Weldon Johnson, settle for writing about pretty things? She didn’t. “Earth,” Spencer addressed the ground beneath her feet,

You’ve had a hard time

bringing it to me

from the ground

to grunt thru the noun

To all the way

feeling seeing smelling touching

—awareness

I am here!

In her poetry, more often than not, the labor of the earth becomes a metaphor–for her work in the Lynchburg community, for the efforts of the Harlem Renaissance and the Civil Rights Movement, for the labor of anyone’s hard life, for growth toward something good.

And the metaphor stretches further. In the beginning of “Earth, I Thank You,” the “it” Spencer thanks the earth for bringing to her is “the pleasure of the garden’s language.” In earlier Bridge of Lament posts, Jeremiah Forshey has talked about how language matters; words matter in this work of communal repair and setting history straight. It isn’t hard to imagine Anne Spencer as high school librarian, bringing the pleasure of language “thru the noun / To all the way / feeling seeing smelling touching” until the students she served grew in “awareness” that they were here–that they mattered.

In another poem, Spencer challenges us to consider the risk of not planting gardens, no seeds sown in the soft, rich soil of a school library or the loam of a sitting room gathering with poets and activists or the actual earth in our own backyards. She writes,

God never planted a garden,

But he placed a keeper there;

And the keeper ever razed the ground,

And built a city where;

God cannot walk at the eve of day,

Nor take the morning air.4

The work of cultivating flower beds and a vision for communal wholeness, involvement in big, national movements and committedness to local young lives: Anne Spencer’s life touched on it all and left us with words that remind us not to “raze the ground” of our life here together, but instead to cultivate a land, a community, a fellowship that is sacred in its wholeness.

Spencer knew that important work happened at home, as close as her back garden, just down the road at the local high school. She set a vision for sowing, tending, cultivating, and reaping the beauty of mended and mending community right here, in Lynchburg, Virginia, among people - not least the schoolchildren, the city’s youth - who need adults to tend to them, who need to hear true words sown in hope and beauty and truth.

Thank God for poems about pretty things.

Questions or feedback? We’d love to hear from you. Email bridgeoflament@gmail.com.

“White Things” White Things - Anne Spencer - My poetic side

“Earth, I Thank You” 10 Poems by Anne Spencer, American Poet | LiteraryLadiesGuide