Day 3: Court Street Baptist Church, Part 1

They worshiped in the same building, but they were not equal.

I said roll, Jordan, roll

Roll, Jordan, roll

My soul'll rise in heaven, Lord

For the year when Jordan rolls

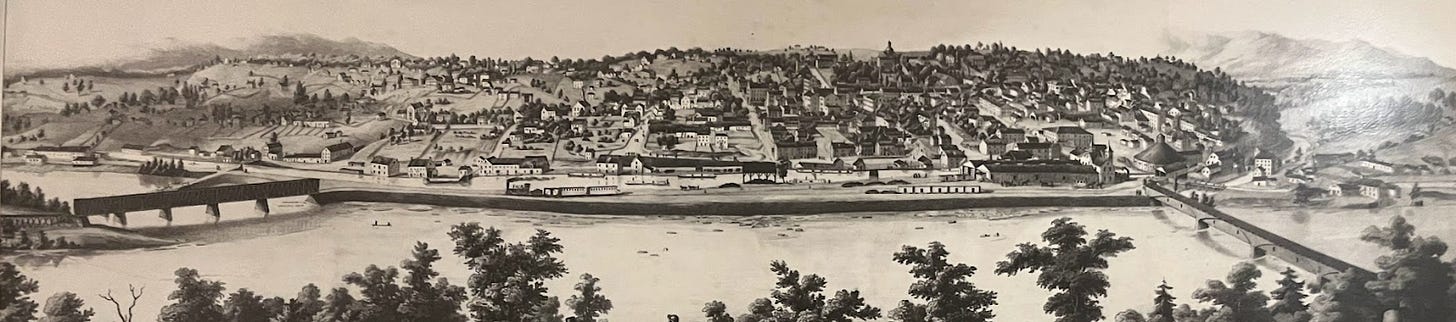

Lynchburg rises high, stepping in terraces one cross street after another from the James River. The origin of Court Street Baptist Church begins near the top of the hill on Church Street, where at the turn of the nineteenth century, the Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists assembled in their meeting houses.

This "City of Hills" was once an up-and-coming tobacco boom town, its muddy streets busy with commerce, including the trading of enslaved persons. Race-based chattel slavery–the fuel for the economic engine of tobacco–had infused the population with one enslaved person for every two free persons by the early 1800s. At one point, a journalist passing through town noted of the Lynchburg tobacco factories, the "operatives are all slaves–male and female, adults and children."1 In this prosperous, white-dominated backdrop, the Lynchburg Baptist Church formed in 1815, soon distinguishing itself as “First Baptist Church.” Over the next seventy years, it grew through three meeting houses on Church and Court Streets. Its final 1884 red brick High Victorian Gothic building sits today at the intersection of Court Street and 11th.

With all the reverence due God’s work through this “place of calm and beauty,” there is an accounting to be told of his people’s complicity with slavery and segregation. Except for the city’s founding Quakers, historic Lynchburg churches perpetuated the same racial hierarchy as other institutions across our nation. The Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists found a symbiotic relationship with the slave-driven tobacco economy. First Baptist Church was one of the first to segregate its members. In the early 1800s, white church members worshiped alongside free and enslaved Black laborers. By the 1840s, enslaved Africans were nearing 40% of Lynchburg's population. In 1842, First Baptist Church “obtained” Lewis, a slave, from an unrecorded source, for $50 a year, to work as a sexton on the church grounds.2

A church leasing slaves was not an unusual practice in Lynchburg. The Methodists also used an enslaved sexton for their property–a man “owned” by clergy of the church.3 As Travis McDonald explained in yesterday's post, “the practice of ‘hiring out’ was complex and integral to slavery and included all types of enslaved workers, all locations, all occupations; and affected all of white society.”

They worshiped in the same building, but they were not equal.

By 1842, the church had built a gallery for “the colored folks” to sit in, separate from the white congregation.4 Baptismal records from First Baptist include the names of free Black people–Aaron Jennings and Claiborne Gladman–and enslaved Black people–Stanford, Peter, Judy, Moriah, William, and Anderson. “Ophelia, the property of Thomas A Holcombe…came forward and was received as a candidate for baptism,”5 “the property of” being a common phrase in the church’s minutes. They worshiped in the same building, but they were not equal.

Local historians Ted Delaney and Phillip Wayne Rhodes have pointed out racial tensions when First Baptist voted to require Black congregants “to remain in [that] gallery after preaching until the white people shall have dispersed.”6 Soon a solution arose, presumably more comfortable for the white congregation, which enabled the Black congregation to claim their own space, even if under the white pretense of “growth”:

"In consequence of the large increase of the colored part of the church, as well as our inability to accommodate in our present house of worship the colored congregation at the same time and place with the white, it is deemed expedient and necessary to provide for the colored people a separate house of worship. Whereupon it was resolved that we proceed to buy or build a meeting-house for the colored part of this church and that it be called the African Baptist Church of Lynchburg"7

In 1844, the Black congregation separated into an abandoned theater on Court Street, which First Baptist repaired into a meeting house. The building skills of the Black community–skills that Travis McDonald shared with us yesterday–were instrumental in this work. Soon after separating, the African Baptist Church petitioned First Baptist to be organized institutionally on their own. Sometime between 1845 and 1846 they were under an official constitution and admitted to the regional Baptist Strawberry Association with 197 members.

Initially, the African Baptist Church worshiped in the repaired theater hall, but adversity struck in 1856, when a fire burned down the building. A tobacco factory across the street accommodated them until a new building could be built.

As was typical of southern Black congregations, African Baptist Church met under white supervision of their parent church, First Baptist. By law, due to fear of insurrection, Blacks could not meet without White supervision. In fact, an 1850 city-wide public ordinance required a night watch and the tolling of the courthouse bell at 9:00pm to call all blacks, slave or free, into homes. But 25 years after separating, and one Civil War later, the Black church called their first black pastor, Reverend Sampson White. At this time, they changed their name to Court Street Baptist Church, and became fully independent of their previous white pastoral oversight.

A touching footnote in our locally divided ecumenical history.

More adversity hit during an 1878 wedding reception, when panic, sparked by fear of a building collapse, led to a stampede for the exit. Eight lives were lost. The day after the incident, The Lynchburg Virginian reported that “The church had been condemned and though repaired was believed to be unsafe, which doubtless increased the panic.”8 Maria Wilson’s burial site in the Old City Cemetery is the only grave known of the eight killed that day. Erected by her brother, who now lays beside her, the bottom of her epitaph reads, “We will meet again.” A touching footnote in our locally divided ecumenical history.

To be continued tomorrow . . .

James M Ellison, Lynchburg Virginia: The First Two Hundred Years (Warwick House Publishers 2004), 33

First Baptist Church, Meeting Minutes, December 12th, 1842, Microfilm available at Jones Memorial Library

Alfred A. Kern, Court Street Methodist Church, (The Dietz Press, Inc, 1951), 10

Blanch White, First Baptist Church, Lynchburg Virginia, 1815-1965 (compiled by Blanch Sydnor White)

First Baptist Church, Meeting Minutes, 1842, Microfilm available at Jones Memorial Library

Phillip Wayne Rhodes Ted Delaney, Free Blacks of Lynchburg Virginia 1805-1865, (Warwick House Publishers 2004), 47

Blanch White, First Baptist Church, Lynchburg Virginia, 1815-1965 (compiled by Blanch Sydnor White), 35

"With all the reverence due God’s work through this “place of calm and beauty,” there is an accounting to be told of his people’s complicity with slavery and segregation. Except for the city’s founding Quakers, historic Lynchburg churches perpetuated the same racial hierarchy as other institutions across our nation." Thank you for not shying away from this. We must not be afraid to look and see.