Despite the burdens of slavery and the racist society they inhabited, Black people in Lynchburg found opportunities for spiritual leadership and education in the Methodist class meeting they held together in the early 1800s.

Black education and literacy in the early days of Lynchburg is difficult to track. The Quakers who founded the city believed it was their duty to teach reading and religion to the Black children in their community, but month after month, they reported their efforts lacking. At the turn of the 19th century, as more people moved into the Lynchburg area and the Second Great Awakening swept through the United States, the religious leanings of the town shifted away from the Quakers and towards Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians. In this new religious landscape, Black people found opportunities for spiritual leadership and education, as evidenced in the earliest records of the Methodist church.

The Methodist Station in Lynchburg began in 1804, and in 1806, a Methodist Meeting House was built on what is now Church Street in downtown Lynchburg. White and Black people worshipped together on Sundays, led by a revolving circuit of traveling ministers, as well as the local lay leaders of the congregation. Enslaved people were generally permitted to attend church on Sundays, their only day off. Both enslaved and free Black people sat in a separate gallery during the Sunday preaching.

One of the distinctive elements of the early Methodist system was the local class meetings1, which were led by lay leaders for the purpose of discipleship and spiritual growth. The Methodists of Lynchburg met in groups for classes, either around the service times on Sundays or in the evenings later in the week. The groups usually had about thirty-five members and would meet either at the Methodist Meeting House or at one of the members’ homes. In these meetings, the members would share testimonies and spiritual insights; the class leaders were responsible for shepherding their souls and fostering biblical knowledge.

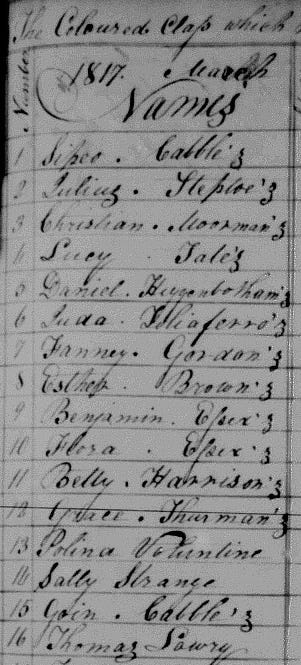

In the early records of the Lynchburg Methodist Station, we find two lists of the members of the Black class meeting: one from 1817 (the first year that records were kept at the Lynchburg Station), and one from 1829 (the second year that records were kept). These records provide snapshots of a dynamic community of free and enslaved Black people who met weekly for worship, community, and religious education.

The 1817 class met on Sundays in the Methodist Meeting House on now-Church Street, after the 3 p.m. preaching. Of the thirty-five members, nine were free and twenty-six were enslaved. The record makes their status clear by including a dark period after the first name of a slave, followed by their enslaver’s last name with a clear possessive at the end:

In the records of the white class meetings, the leaders are noted in the first spot on the register, with “C.L.” (Class Leader) following their name. While the 1817 Black class meeting didn’t have a class leader formally recorded, it’s likely that Sipeo, enslaved by the Cabell family, was the leader for the class, since his name is first on the register. Julius, who was enslaved by the Steptoes, may have served as a secondary leader.

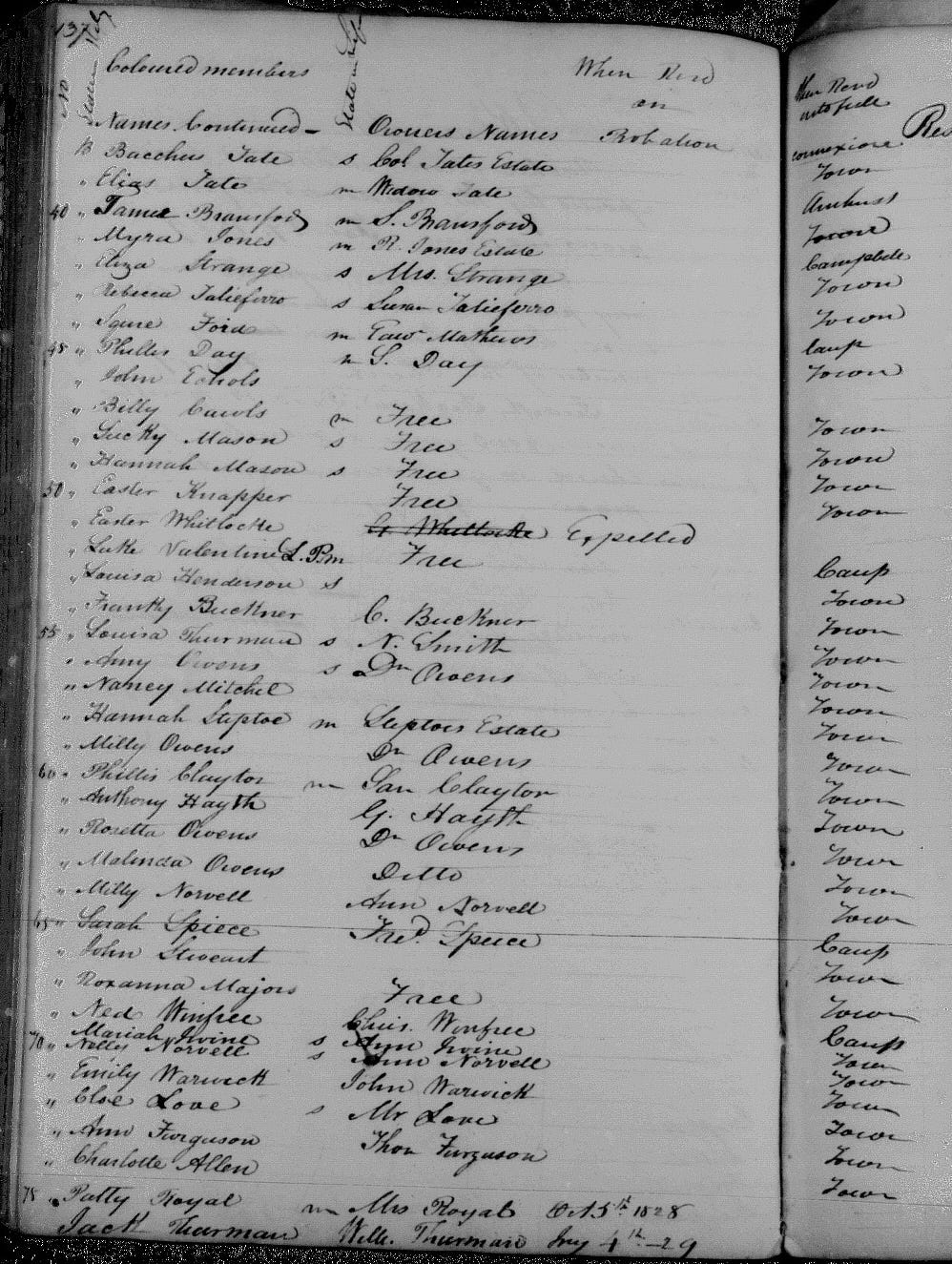

Although Ethelbert Drake, the pastor in 1817, implores the future pastors of the Lynchburg Station to keep careful records, the next pastor to keep a membership record was William A. Smith, recording for the year 1828-1829. He records seventy-seven “Coloured members,” listing their baptism status, their name, their marriage status, the name of their enslaver, when they joined the meeting, and where they lived. Seventeen were free, fifty-three were enslaved, and seven are missing their freedom/enslavement status.2 Ten people had been members of the 1817 class.

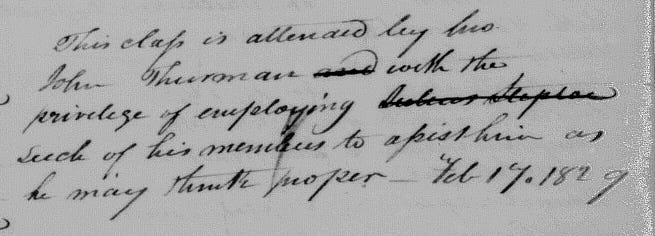

Julius Steptoe, now freed, appears first on the register, followed by his wife, Winny. On the righthand page, Smith records the following remark:

“This class is attended by bro John Thurman

andwith the privelege [sic] of employingJulius Steptoesuch of his members to assist him as he may think proper — Feb 17. 1829”

Although Smith attempted to strike Julius Steptoe’s name from the record, his initial inclusion reveals that Steptoe was likely the primary Black leader of this class meeting. It’s uncertain how involved John Thurman was. White leaders at the time often recognized that Black ministers were more effective at pastoring Black church members, and it’s entirely possible that Thurman left Steptoe to lead the class as he wished.

At their Sunday class meetings, the Black church members shared their spiritual lives with each other. They prayed together, found solace and encouragement in their spiritual and temporal troubles, and probably read the Bible together. In her book “When I Can Read My Title Clear”: Literacy, Slavery, and Religion in the Antebellum South, Janet Duitsman Cornelius argues that literacy across the South was more prevalent than we often imagine, even among enslaved people. White Christian slaveowners felt an obligation to pass along Christianity to those they enslaved, especially in the early antebellum period, which was rife with religious revival. Christianity’s careful attention to the Word of God necessitated literacy, and for a time religion was a sanctioned space for the limited education of some Black people, especially preachers.3

As a spiritual leader among the Black Methodists in Lynchburg, Julius Steptoe was probably able to read and write; he was certainly able to sign his name to one of his wife’s manumission documents. It’s likely that several of the Black Methodists in Lynchburg were literate, especially those who were free. They may have even used the class as an opportunity to teach each other, especially in the early years of the class—teaching an enslaved person to read wouldn’t be outlawed in Virginia until 1819.

There are no records of the Black class meeting after 1829; the pastors of the Lynchburg Methodist Station decided to only record the white membership rolls starting in 1830. However, Black people still attended churches, forming essential sacred community with each other, perhaps in unrecorded class meetings. The legacy of the class meeting lived on years later, with Black Methodists around the city dedicating Jackson Street Methodist Church in 1869, the first Black Methodist Church in Lynchburg. Jackson Street Methodist Church would play a vital role in Black education after the Civil War. The church hosted a Freedmen’s Bureau school during Reconstruction, as well as the first Black high school in Lynchburg in the 1880s. Their efforts continued the legacy of the Black class meeting that gathered half a century before.

The records of the Black Methodist class meetings are preserved on microfilm at Jones Memorial Library. Records of Centenary Methodist Church, Records of Methodist Station 1817–1843, pages 29, 135–140.4

Rebecca Pickard is a writer and researcher based in Lynchburg. She serves as a researcher for the South River Meeting House and Burial Grounds Committee as it seeks to develop new programming and to plan for the long-term future of the site. Her research focuses on the abolitionist efforts of the South River Quakers and the histories of the free black residents of Lynchburg.

For more information about Methodist class meetings, see “The History and Significance of the Wesleyan Class Meeting” by Jon Earls and “The Sinew of Early Methodism: The Class Meeting (Part 1)” by Bob Johnson.

Charlotte Allen is counted as free here. Smith doesn’t record her status, but on an 1819 Free Negro Register she is recorded as “born free” in Campbell County around 1801.

“…most African-Americans responded to religion only when it was preached by one of their own. Recognizing that black leaders were the only way to get black acceptance for Christianity, white religious leaders gave in and recognized black religious leaders among slaves, in many cases allowing them to learn to read or teaching them,” Cornelius, 86. See also 105-107.

Thank you for this historical account, Rebecca! It's fascinating to know that teaching enslaved Blacks to read and write was tolerated in Lynchburg, particularly since so many across the South believed literacy made them much more difficult to control. Indeed, Frederick Douglass heard his master, whose wife was teaching Douglass the alphabet before the husband found out, declare, “It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable and of no value to his master.” Douglass said, “From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom," which was literacy. He would later write:

"The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers."

"As I writhed under it, I would at times feel that learning to read had been a curse rather than a blessing."

"It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy."

"It opened my eyes to the horrible pit, but to no ladder upon which to get out."

Of course, we know he eventually escaped and grew to become an abolitionist and one of the great orators and writers of American history. We must continue his legacy and advocate for teaching all of American history so that future generations will be spurred by that knowledge to make their world better.

This is such an important history! Thank you for this work, Rebecca. It's especially powerful to read the names in the documents.