Please note, there will not be a Bridge of Lament post tomorrow (Sunday, June 22nd). Enjoy resting with friends and family during this Liberation Season, and look for the next Bridge Crossing installment to land in your inbox Monday morning.

History is not the whole story of anything, but the beginning of everything.

There are no records of schools for African Americans operating in Lynchburg

before the Civil War, as neither slave nor freedman was allowed lawfully to be

educated, though some had found ways to learn to read and write and were ready to

begin teaching almost immediately after the war. After the War ended in 1865, a bureau was established by Congress to help supervise the relief and education of ex-slaves & refugees: the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The South surrendered in April 1865, and the very next month in Lynchburg, three freed slaves set up two “self-supporting” schools for freedmen. These schools were staffed by three black teachers, all believed to be former slaves themselves: Robert A. Perkins, Jr., Samuel Kelso, and Daniel White. The term “self-support" was used on Freedmen Bureau records throughout the South and meant that students paid whatever tuition they could afford to attend the schools, and the black communities provided facilities for the school sites. The Bureau gave partial support in the form of teacher salaries and rent for facilities. These facilities evolved from outside areas under trees to a room rented in someone's house or basement. An article in the Daily Virginian newspaper in May 1866 praised the work of Robert Perkins, Jr. after, an annual school exhibition in which his students did so well.

In March 1866, a new school opened at Camp Davis in Lynchburg. Camp Davis, originally a Confederate mustering ground, was later the Union Army's local installation for keeping guard over the freedmen to ensure their safety and freedom. The Bureau sent Jacob E. Yoder, a Mennonite from Pennsylvania, to teach at the school for freedmen. With little help or equipment, he opened a school on the Camp Davis site and welcomed blacks who desired an education. Many of the classes held at Camp Davis were in what appeared to be shacks on the campground, until later classes were held in the basement of Jackson Street Methodist Episcopal Church.1

Foundations sprang up across the South, establishing funds that broadened the concept of education for the freedmen, as well as whites. The Peabody Education Fund and other boards supplemented teachers' salaries, built new schools, and purchased new equipment. These free schools were established in Lynchburg for blacks well before public schools were established in 1871.

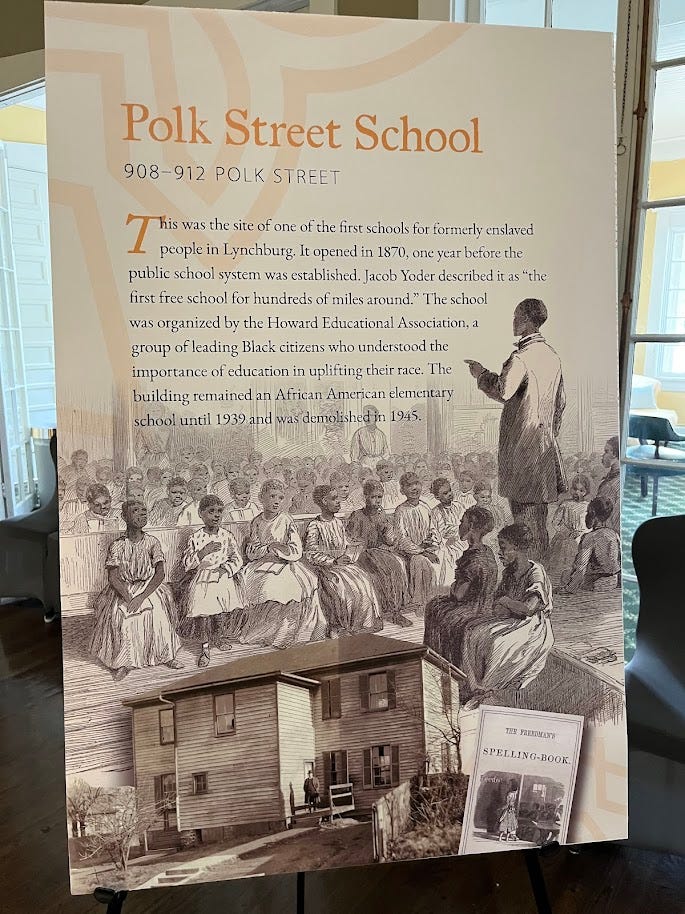

As a result of their enterprise, during the 1868-1869 school year, freedmen owned four of the six school buildings. One of them, Polk Street School, between Ninth and Tenth on Polk, is the oldest school building on record for blacks in Lynchburg. The public history project Silent Witnesses is marking this site in its “mission to document the enslaved experience of people of African descent and related sites in Lynchburg Virginia.” The Lynchburg Museum System also notes, “The building had formerly been one of the barracks buildings at the Confederate Camp Davis in the 900 block of Polk Street and was known as the ‘first free school for hundreds of miles around.’”2

By 1870, the new Virginia State Constitution passed a law for a uniform system of public free schools. The Freedmen’s Bureau began closing its offices and pulling its resources out of the southern states. Only two of the four schools remained open after the summer of 1869. Robert Perkins became the secretary of the Board of Trustees, whose task was to find a suitable lot on which to build a bigger and more permanent school structure. He and Jackson Street Methodist Episcopal Church (JSMEC) set out on that task.

On July 1, 1870, the last official report was issued from the Freedmen's Bureau as it ended its management of the schools that year. The report noted the progress made by the schools throughout the state. The report also noted the flourishing of the Lynchburg normal schools, in which Jacob Yoder served, also noting the thirty pupils being trained to teach.

By this time, there was stability in Lynchburg schools. Tuition payments from freedmen still supported the schools. These were permanent black schools in which students were taught by black teachers and white northern teachers. One normal school class was being maintained to further educate freedmen to meet the growing demands for additional teachers throughout the state. On April 5, 1871, nine state-funded schools opened in rented buildings, and Jacob Yoder became the principal of the three black schools: the Polk Street School, the House on Franklin Hill, and a building on Franklin Hill.

If any student who finished the Polk Street school desired to be taught at a higher level, Jacob Yoder veered off his own set curriculum and taught secondary education to those students. At first, there were only three students interested, but soon the number increased, and a formal high school for Black students was finally established in 1881 by Jacob Yoder and the members of JSMEC. The high school was located in the Jackson Street public school building, directly across Ninth Street from the church (now Jackson Street United Methodist).

The church recognized society's responsibility to educate children, with various ministers leading in that struggle during the 1800s. As mentioned earlier, JSMEC was host to the Freedmen's Bureau school during Reconstruction, holding classes in the basement of the church and graduating its first class in their neighboring Jackson Street Colored High School in 1886. JSMEC advocated for Virginia children and the professionalism of teachers through two associations of educators for quality public education—the Virginia Teachers Association, a black organization organized in Lynchburg at the church, and the "normal" schools.

In these early years, Virginia conducted summer schools to assist in improving the skills of teachers. These summer schools, sometimes referred to as the normal institutes, were conducted separately for black and white teachers. Again, JSMEC would lead by letting the church facilities house the institute for the normal schools. This was the first institute in which a summer normal school for colored teachers was held. Black professors from Richmond and Petersburg conducted the courses and classes alongside teachers from Lynchburg.

Many educators who were members of the JSMEC played a pre-eminent role in early African American education in Central Virginia. Frank Trigg, Jr., a former slave and contemporary of Booker T. Washington and a member of the church, was one of the co-founders of the Virginia Teachers Association, then referred to as the Virginia Reading Circle for black teachers.3 Frank Trigg played an important role as Chairman of the committee on Arrangements and Correspondence for the Summer school. Many black teachers from out of town attended the institute in Lynchburg, utilizing boarding houses and private facilities that provided boarding. The committee assured the visiting teachers that they would be welcome in Lynchburg. Initially, 94 teachers began their summer school here. Soon, enrollment nearly doubled, as 184 enrolled.

“That the negro teachers of Virginia organized themselves into an association as early as 1887, is a remarkable achievement, only 25 years before, the state of Virginia made it unlawful for a Negro, free or slave to learn to read or write,”

…writes an author of the history of the Virginia Teachers’ Reading Circle (which, after six name changes, finally became the Virginia Teachers Association)

Frank Trigg retired from public service in 1926, before his death in 1933. In 2012, a historical marker was placed in front of his former home on Pierce Street.4 Trigg is buried in the Old City Cemetery on Taylor Street.

History is not the whole story of anything, but the beginning of everything. In Part 2, on Tuesday, June 23rd, I will endeavor to tell you the beginning of Yoder Elementary School, the heartbeat of its community, and give the needed honor to the women and men who struggled there to educate the many African American students of Lynchburg.

Beatrice Hunter, a retired Lynchburg native, has a passion for local Black history. She attended the beloved Yoder Elementary School in Tinbridge Hill, and has been published in Lynch's Ferry Magazine | A Journal of Lynchburg History - Memories, Fond and Painful, of Black Bottom. Bridge of Lament featured her writing last year in Day 13: What's in a Neighborhood? - Tinbridge Hill.

In addition to teaching there, Yoder was also listed as Principal of the Camp Davis School and initially had four teachers under his supervision. In the meantime, Yoder gave private tutoring lessons to Robert Perkins, Jr., to help further his education in his quest to teach at a higher level, teaching "normal" school classes or classes set up to train blacks to become teachers. Daniel White left the school after the first year. Samuel Kelso became active in politics and served as a colleague of Jacob Yoder. The two schools begun by Perkins and the others were maintained throughout the Reconstruction period. The growth of black schools in the South helped to establish better-qualified teachers and new schools. A stimulus came in the form of philanthropy and the help received from church denominations. Baptists were working to create and oversee black schools.

An article in Harper's Weekly in 1886 shared, "and there is a complete

system of graded schools; these schools contemplate a period of ten years' study-four years in

the primary department, three years in the grammar, and three in the high school. The races are in separate schools, there being three district school-houses for whites and four for blacks, In

the white schools are 1350 pupils, and in the colored, 1300; the high school for whites has 125,

and the colored high school only 17, but the number in the latter is increasing."

Thank you, this is excellent and so informative!