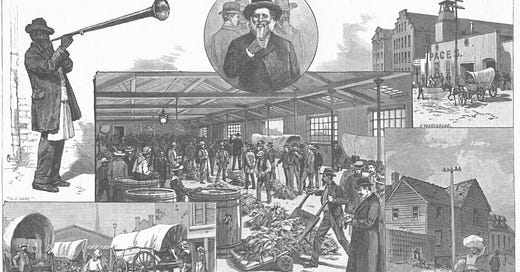

Day 3: Tobacco Town

An article in an 1886 issue of Harper’s Weekly, illuminating the prosperous post-war Hill City, tells the reader that “Lynchburg . . . was the origin of a poem that made its name familiar throughout the land.” The verses open in a mimicry of African American speech:

I’s gwine down

To Lynchburg town

To tote my tobacker down dar.’1

The article closes proclaiming that “the town certainly has its face set toward a fine future in which its present prosperity will not only increase, but all the finer results of wealth will be developed.”2

1886 was the year Lynchburg celebrated its centennial, a year in which the city was the largest loose leaf tobacco market in the world.3 But the article erases the contributions of the enslaved people alluded to in the pre-war poem’s condescending lyrics; instead, it reports a one-sided post-war sentiment that “both races, being bent on enterprise and improvement, work harmoniously together, and with good feeling.”

From the beginning, Lynchburg was a slave town, built on the James River to capitalize on Virginia’s burgeoning tobacco market. The town’s early growth was solely due to tobacco warehouses that prepared goods for delivery down the river to market in Richmond. A journalist passing through town in 1859, noted, “You can hardly turn into a street without seeing tobacco factories.''4 The muddy streets of the City of Hills’ up-and-coming tobacco boom-town were indeed busy with commerce, including the trading of enslaved persons.

Slavery was the fuel for that economic engine of tobacco. The same visitor observed that the “operatives are all slaves - male and female, adults and children.”5 Historians at the Lynchburg Museum tell us, “By 1860 the city of Lynchburg was not only home to one of the largest concentrations of enslaved factory workers in Virginia, but it was also a major site for trading and auctioning enslaved people in the state.”6

The year Harper's Weekly ran their piece on “Lynchburg town” was probably the height of the city’s tobacco market. The economic prosperity from tobacco labor set a foundation for the white business class’s continued wealth accumulation. Historian Phillip Scruggs explains, “Money made in the tobacco business began to go into the wholesale merchandising companies, into various manufacturers such as shoe making and textiles.”7 By 1915, during Lynchburg’s transition to shoe manufacturing, the city’s wealth per capita was third in the nation.8

Harper's Weekly got it right in 1886 that Lynchburg was “familiar throughout the land.” What the Harper’s article failed to clarify is that it was the wealth generated by enslaved people that brought Lynchburg’s name to prominence.

Now that I know where the money came from, my pride shatters with lament and anger, for the way people in this city were separated, sold, and controlled for the economic benefit of those in power.

I call Lynchburg home, and before I had any concept of where the early money came from, I would proudly tell my friends and family that in days past, Lynchburg ranked amongst the wealthiest cities in the U.S. per capita. Now that I know where the money came from, my pride shatters with lament and anger, for the way people in this city were separated, sold, and controlled for the economic benefit of those in power.

I want to reclaim the erased part of the Hill City’s history for the honor of those who’ve been left out in its telling, and to open the conversation about what can be given back.

Note from the Project Coordinator: the email version of these posts has previously included a button to pledge financial support. This project is free as a service to our city, and we will not be asking for donations. Please bear with us as we navigate Substack, and ignore that pledge button if it appears again.

The poem referenced in Harper’s was popularized by, among others, the Christy Minstrels, a blackface group who performed steadily in New York City throughout the 1840s.

Warner, Charles Dudley. The Industrial South. Harper's Weekly, December 4th, 1886.

Elson, James. Lynchburg Virginia: The First Two Hundred Years. Warwick House Publishers: 2004, p.222.

Elson, p.32.

Elson, p.33. The factory workers included some free blacks as well, though the visitor certainly may not have perceived that difference.

In fact, despite the generally low opinion of slave traders even in a slaveholding society, one slave trader, Seth Woodroof, “whose career . . . spanned at least two decades, served on city council from 1859 to 1866, and was apparently considered a solid citizen by his fellow Lynchburgers.” (See James Elson, Lynchburg, Virginia, 42). The Lynchburg museum notes that Woodroof had the “most active and infamous slave trading business in Lynchburg, circa 1830-1860.” Slavery in Lynchburg — Lynchburg Museum System

Scruggs, Phillip Lightfoot, A History of Lynchburg 1786-1946. J.P.Bell: 1950. Requoted by Laurant, Darrell, A City Unto Itself. Darrell Laurant and the News Advance: 1997, p.66.

Laurant, p.66.