Day 4: Court Street Baptist Church, Part 2

Lynchburg was, and is, a city that belonged just as much to the congregants of Court Street Baptist Church as anybody else.

Roll, Jordan, roll

Roll, Jordan, roll

My soul'll rise in heaven, Lord

For the year when Jordan rolls

Hallelujah!

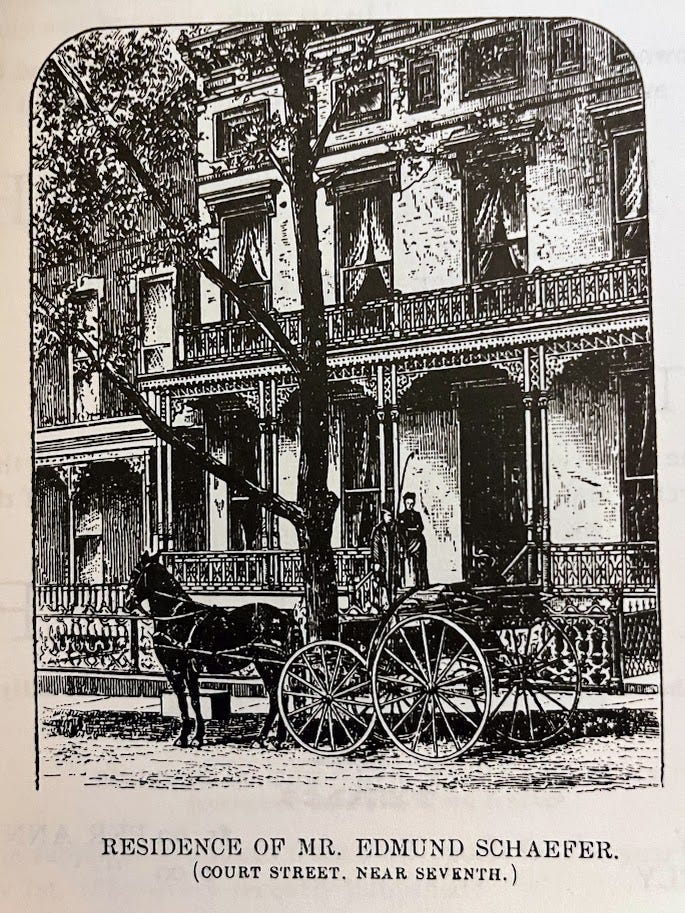

Though the collapse that led to the stampede was a false alarm, Court Street Baptist, emotionally and physically wounded, committed to rebuilding on Courthouse Hill. But they faced more adversity to get there. The wealthy of Lynchburg found Court Street a desirable place to live. The street was busy with the carriages of the city's most prominent citizens. These were large Victorian homes with beautiful parlors, libraries, and dining rooms, run by housekeepers, maids, and stable hands, and adorned with beautiful portraits and oil paintings, rosewood pianos, and gold leaf mirrors.1

The maids and servants in and around these homes were Black. Black domestic laborers cleaned, cooked, carried the groceries, and tended to the children on Courthouse Hill in the post-Civil War era. Others were stable hands or carriage drivers navigating the rutted and muddy streets, later paved with cobblestones, and greeting the playing children, and tending to the horses. Many of these cooks, stable hands, nurses, and drivers worshiped together on Sunday mornings in the Black churches of Lynchburg, and the largest gathering was the Court Street Baptist Church.

Before the Civil War, Whites had a vested interest in keeping their slaves close, but now they were more interested in pushing Blacks away from public life. But Black Lynchburgers had lived, worked, and worshiped on Court House Hill for their whole lives and were not about to give up their claim. After the fire, church members pulled together their savings to buy a community cow pasture at the end of the street on which to build, but their wealthy white neighbors tried to prevent the transaction. The remarkable story behind the congregation's resolve to occupy this space is told well by their own historians:

“When it was discovered that the Court Street congregation was interested in the parcel of land at Sixth and Court Streets, the residents of Court Street offered the owner many times more than what he had agreed to charge the congregation. The church offers, however, had been wise enough to bind the bargain by securing the option with a $100 down payment, and agreed to pay the balance of $2,400 in a given number of days. Discovering this, the Whites then appealed to the banks to lend no money to the church to pay for the property so that the church would lose its option agreement. After the pastor, Reverend Fielding Morris, and the church officers received this information, they immediately informed the congregation.”

The church members gathered and put in motion a plan that thwarted the white community:

It was determined that it would be necessary for members to contribute money to purchase the property. At that time Blacks did not trust Whites nor their banks. For this reason, their meager life’s savings were stashed at home in mattresses, wrapped in socks and in small bags hidden in attics or in cavities over mantles. Answering the appeal of church officials, the members rushed home and returned with their small life’s savings in such amounts that it filled several wash tubs. Because the officers had no time to count the money, it was carried to the bank in tubs. They arrived at the bank two hours before the deadline. After bank officials counted the money, it was discovered that not only was there enough to pay the balance on the property, but there were several thousand dollars left for the building of the church.2

Black workers, active in the carpentry and masonry trades in the city,3 were the sole laborers in the building's construction. John Williams, a black carpenter from Appomattox County, built houses in Lynchburg in the years after the war that freed his people. Local historian Harry S. Ferguson locates his name on several property deeds in the city including on Fifth Street, Thirteenth, and Filmore. In 1879, he supervised the construction of the Court Street Baptist Church building. Williams, also a deacon of the church, went on to run for City Council in the late 1880s and became one of the five black leaders elected into office.4

Court Street Baptist’s new building, which stands today, rose prominently over the city. It was the city’s largest church and its highest spire. The location and the spire shouted an important message over the rooftops: Lynchburg was, and is, a city that belonged just as much to the congregants of Court Street Baptist Church as anybody else. Their building was poised to carry its people through the social, economic, and political upheavals, gains, and struggles coming in the next century.

To be continued on Monday, June 24th . . .

Link here for “Court Street Baptist, Part 1.”

Annie Gilliam Conrad, The Street Above the Steps, McClure Printing Company 1954, pg 8

Mary Louise Williams, A Brief History of Court Street Baptist Church, 1998.