The following glimpses aim to pay due honor to many of the women and men who struggled to educate African American students in Lynchburg at the Yoder School, located at 103 Jackson Street.

“give them a gem, call it Yoder, and watch them shine…”

There is no yearbook noting the attendees of Yoder Elementary School in Lynchburg. Such a simple statement, and yet one which haunted me and left a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach constantly, whenever I ventured past 201 Jackson Street, where the school had stood for over 66 years as a jewel in the black community of Tinbridge Hill. After all, its only claim to fame was having been one of the vanguards of free public education for blacks in the still-segregated town of Lynchburg. The school had been the heartbeat of a community. The school nurtured multiple generations of African Americans, at a time when the town was still struggling to know just what to do with its freed slaves and black citizens.

Jacob Yoder

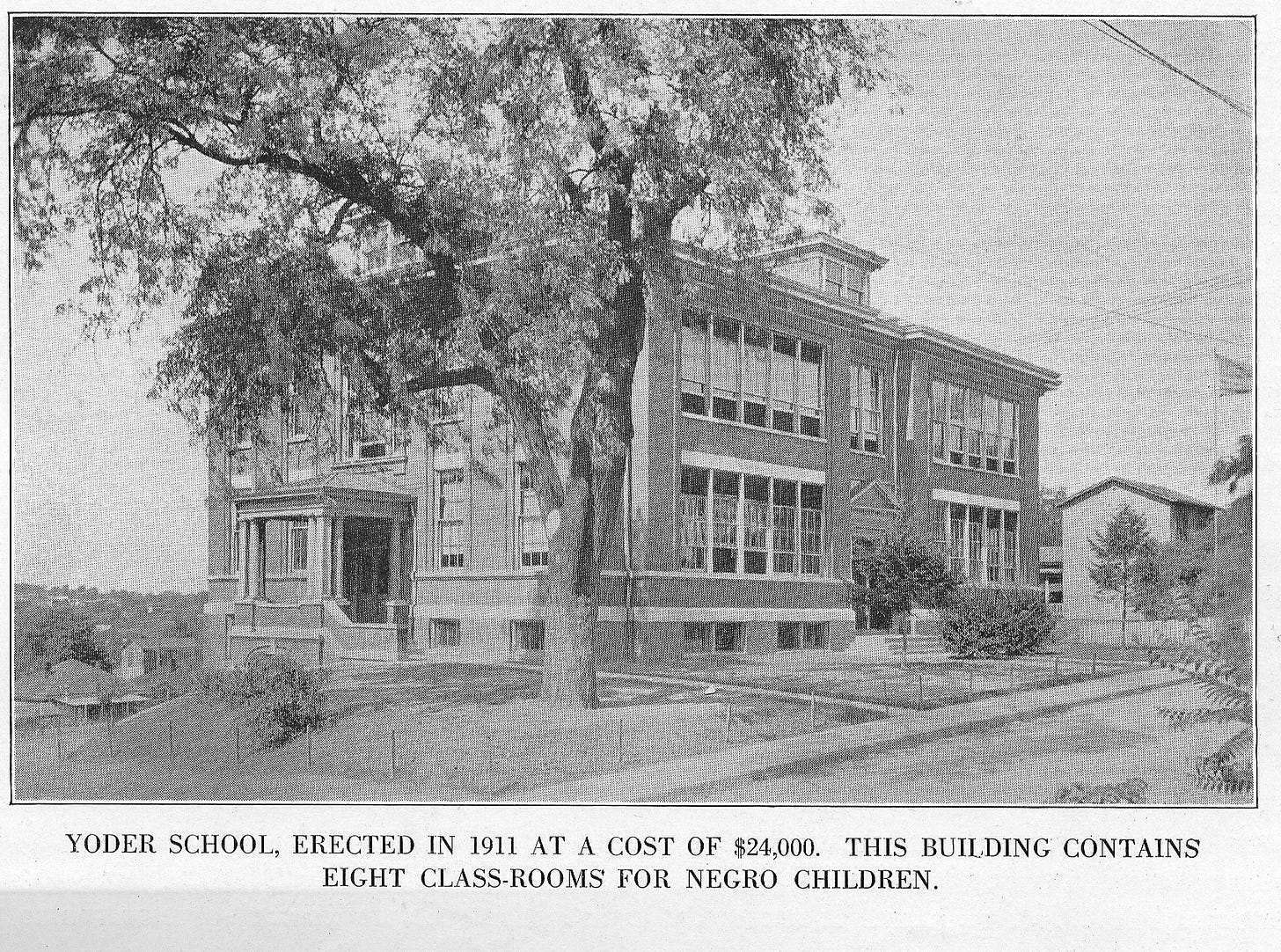

As noted in “Black Schools in Lynchburg 1865-1900,” Jacob Yoder arrived after the Civil War, and, in 1872, a new school for colored boys and girls was built on Seventh and Jackson Street: the Jackson Street School. Through the ensuing decades, the enrollment grew larger, and classes soon filled to capacity with children vying for an education.

Jacob Yoder had, by the turn of the century, given his all for the education of the colored children in Lynchburg and began to suffer from bad health. At his death in 1905, Yoder was praised by teachers at the Payne, Polk, and Moorman schools, not to mention the whole of Lynchburg's black citizens. Obituaries stated that “His life was laid upon the altar of devotion to the elevation of our race by that most potent measure, education.” He had,” they declared, “devoted his life unselfishly and unstintingly to our race and wore himself out in the service to us.”

Five years after the death of Jacob Yoder, a new school was named in his honor, the Yoder School, built at 201 Jackson Street in 1910, in Tinbridge Hill.

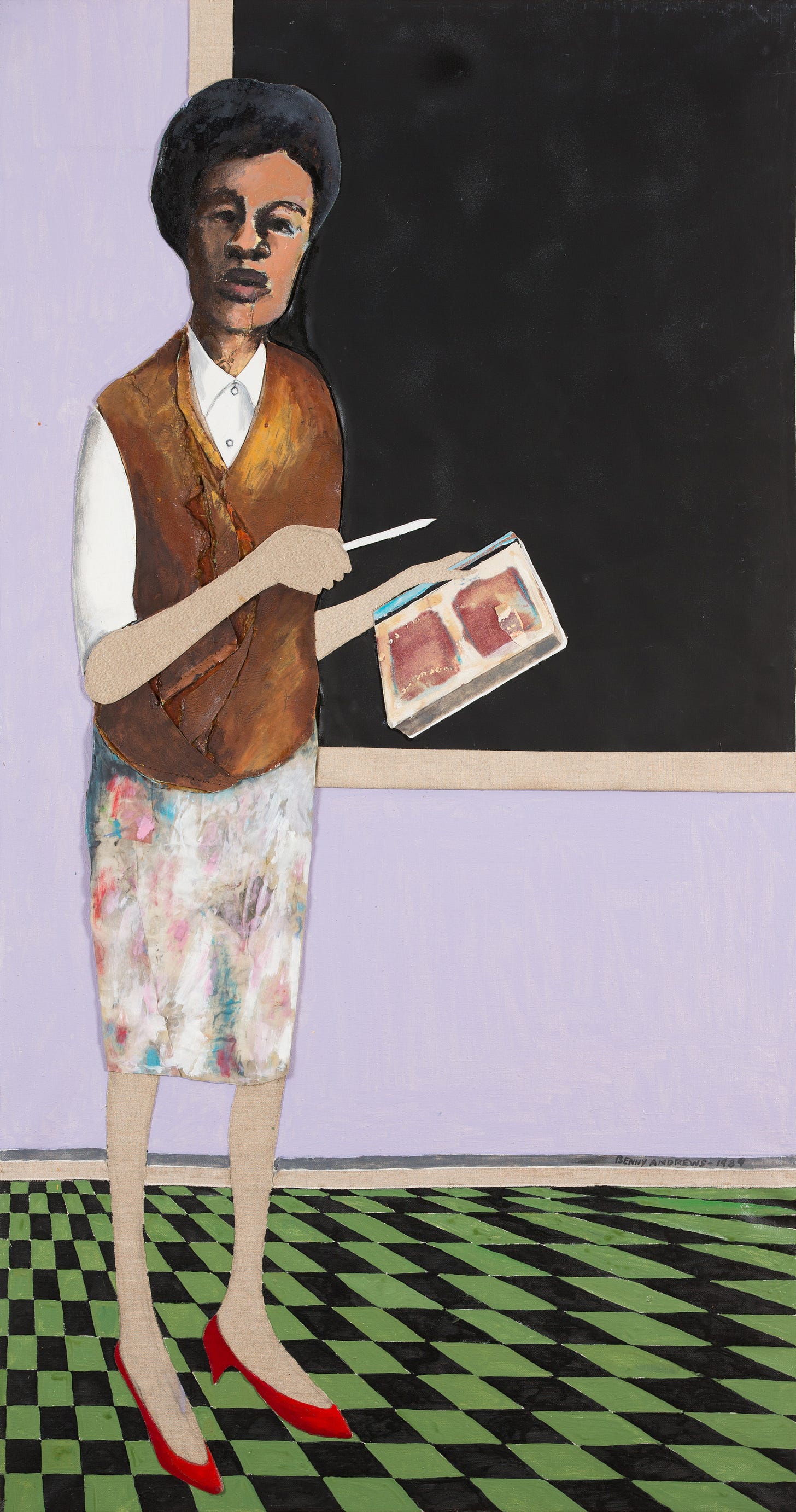

Ms. Sallie Frank "Frankie" Anderson

How can anyone ever write anything about Yoder Elementary School and not give thanks to all those women and men who dedicated themselves to the education of the segregated Black children in their charge—Perhaps not only at Yoder, but in all of Lynchburg City Schools? It is a consensus from all today who remember her that Ms. Sallie Frank “Frankie” Anderson was by far the kindest and most dedicated teacher ever at Yoder.

Miss Anderson was born on October 9, 1904, a year before the death of Jacob Yoder, the “creator” of the school she would come to love for the rest of her life. Miss Anderson was a lifelong member of the Tinbridge Hill neighborhood of Lynchburg, having been born and lived at the furthest end of the neighborhood at 1113 Hollins Street. She was one of three children born to William and Lillie Jones Anderson, with siblings Dorothy “Dolly” Anderson and John Louis Anderson. Mrs. Anderson was a former student of Yoder, and after completing her necessary higher education, graduating from Lynchburg's Negro High School—then Jackson Street High—and also the Virginia Seminary and College, she received her BA degree from Hampton Institute.

Miss Anderson died on October 22, 1986, of what was called a cerebrovascular accident. She was 82 years old. Miss Anderson is buried in a family plot with her family at the Old City Cemetery on 401 Monroe Street in Lynchburg, not far from her home. Thank you, Miss Anderson. Rest in eternal peace.

Beloved Community Members

Mr. Brown had lived on Polk Street possibly all his life. He was a member of the Parent Teachers Association for Yoder and a member of the Tinbridge Hill Improvement Association. Mr. Brown freely gave of his time, attention, and funds for any improvements he could make for his community. He was instrumental in working alongside others in securing a Fountain, Tot Lot, and building fixtures for the students at Yoder.

Another community member who equaled all others in working for Improvements for his school and community was Mr. Raymond White. Mr. White was a lifelong resident of Tinbridge Hill and had attended Yoder in his youth. He now had children attending the school and was determined to do all he could to make sure they were getting the best educational social setting possible. His son Michael White tells the story of how his father had him and the other boys in the community clear a wooded, trash-thrown area atop Monroe Street to make the area a Tot Lot, giving the younger children an alternative area to play than the schoolyard.

The schoolyard had at times been crowded with boys shooting hoops, or children racing, and the Tot Lot would be just for them. Somehow, according to Michael, he had the impression that the older guys clearing and cleaning the Lot would be able to use it to shoot basketball, but alas that was not to be. “We had done all that work and couldn't use the Lot,” Michael humbly admitted. Well, back to the schoolyard.

Mrs. Jordan and May Day. May Day was a celebration of spring every May 1st at Yoder, like all the other schools in Lynchburg. It was also a time to reward the students who had done well in health, as it was also a reminder of the “5 Points of Health.” The May Day “court” got to make their own paper five-point crowns to wear. This was a day when all the girls dressed up in fancy dresses and patent leather shoes, and the boys came to school with a white shirt and tie.

One year, to my surprise, I was awarded to be in the May Day court celebration. Bummer. My family was poor, and I didn't own a fancy dress or shiny shoes. After learning the news that I would be one of those students out on the playground in full view of the whole school, I must have been sullen for two days. Just about the time I had finally reached the conclusion to just tell Mrs. Jordan I couldn't be in the celebration, she asked me to stay after school. Staying after school could only mean one thing: I was in trouble. But what had I done?

After school let out, I strolled up to Mrs. Jordan's desk. Her head was bowed over someone's lesson. I smile as I recall all of this, as I really think Mrs. Jordan had the heart of a saint and the patience of Job. I silently hoped she had forgotten what she had asked me to stay for. It was then that she reached behind her desk and pulled out a paper bag. “Don't open this bag til you get home with your mother,” she said. I nodded my head, and upon reaching home, I gave the bag to my Mom. Mama reached into the bag and pulled out one of the prettiest dresses I had ever seen. The “criminal” slip was made onto the dress, and it seemed to burst open like a flower during a spring rain. My eyes grew huge, and I couldn't speak. Then Mama reached into the bag again and I wondered what ever could be in there now? She pulled a beautiful pair of black T-strap shoes out, and after convincing her that I had not asked Mrs. Jordan for these gifts, she let me try them on—perfect fit!

How did Mrs. Jordan know my sizes? When did she get these, and why me? Mama handed me back the bag, and I hung up my dress, now in anticipation of being the best-dressed girl at the May Day. The next day, Mrs. Jordan made no mention of the gifts till class was ending for the day, on my way out of the door, she asked me, “Did they fit?” I nodded my head and whispered thank you.

Mrs. Nancy Goldsberry Meadows taught me in the Second Grade. And as hard as I try, I can't recall her ever without a smile, even though admittedly I was not one of her easier students. It seemed to me that none of the students in her charge could do any wrong, as long as they showed a penchant for trying to learn. I can recall the one time that she had to scold me for refusing to participate in class. Not raising her voice above a whisper, she called me up to her desk and asked me in a whisper, “Why are you acting up today, Beatrice?” She noticed that I struggled to find an answer to her question, so she then said, “What is it that you need? And if you can't think of anything, then you should go back to your desk, take out your work, and begin, don't you agree?” Mrs. Meadows was more like a mother figure than a teacher and taught for forty years in the Lynchburg Public Schools. I have to think that the love she showed us was akin to her religious dedication to her church, and the love everyone felt for her was not to go unnoticed.

On the 153rd Anniversary of Court Street Baptist Church in 1987, Mrs. Meadows was presented the church's first Annual Vernon Johns Citation Award, the highest honor the church bestowed on any person. Mrs. Meadows had given over fifty years of dedication and service to the church. Although she had graduated from the Virginia Theological Seminary and the Hampton Institute, after she retired from teaching, she returned to business school and became the first Office Secretary of Court Street Baptist. For many years before and after she had served as the church pianist, the directress of the Children’s Choir, and sung in the Senior Choir. Along with her service and teaching to the church, Mrs. Meadows was an ardent member of the NAACP, the AKA sorority, the Eastern Stars, Hill City Flower Club, and the Glossilla Art Club. According to an article in the Lynchburg Area Journal, dated September 9, 1987, Mrs. Nancy Meadows bid her final farewell in a health facility in Dallas, Texas. Heaven reclaimed an angel; we who remember her lost a Queen Mother. For the woman, teacher, parent, servant, and friend that she was, we are forever grateful.

Yoder Playground Remembered

The playground of Yoder School was always filled with the hopes and dreams of its users: children who attended the school and children from varying neighborhoods. There was just something about Yoder that seemed to attract them. Not many people who lived in the neighborhood surrounding Yoder School could ever forget the playground dances. Mrs. Hubbard would set up the 45-rpm record player next to a cooler of sodas, and the fun would start. Ribbons tied on meager plaits would come off, replaced by foam-roller-set bangs to look more mature for a girl's childish crush. Someone's father was sure to notice his Old Spice aftershave had been “borrowed" by his young son; it “spoke” very loudly. Mrs. Hubbard was loved by all her charges, so though she was carrying out her duties for her job, she didn't make any difference to us; she was “our Mrs. Hubbard” for those hours, remembered with love even sixty years later.

Whether it was the weekend playground dances given by Mrs. Marjorie Payne Hubbard through the Parks and Recreation Department or a spontaneous softball or football tournament to test the skill of other kids from other neighborhoods, like the saying goes, “If we build it, they will come” Even later, years after the school had closed and the look of abandonment shadowed its porticos and corridors, the youth that had grown up in and around Yoder, now adults, found themselves still shooting hoops on the basketball court or simply standing as if in guard of the playground.

Yoder's attraction seemed to bring the young and the old back to see it off and hold its memories. Many nights after the sun had long gone down, you could hear the thump of a basketball dribbled in the dusk, and wonder who was playing ball now, and why at our Yoder?

At times under the corner streetlight, in the warmth of a summer night, a group of guys with imagined talent for singing a Capello would harmonize the latest song heard on the radio, or perhaps members of a local teen band would rehearse and practice on either end of Jackson Street and Yoder grounds. Over the years, people from other neighborhoods with far more sinister intentions found their way to Yoder grounds, it was then that the dice games, drinking, and other nefarious acts soiled the respectfulness that we in the community held for our illustrious school and area. This intrusion met with strong opposition from neighbors and former students now trusting their own children to the playground's ever care, and the police were often called. What these newcomers did not nor could not understand was that for us, Yoder's children, the school and area represented a time of community, a sense of unity, and memories of fortitude sacrificed and worked for since well before 1911. Yoder School was our beginning.

Yoder Reborn

Over the years, people who have been charged with its care and oversight, like Marjorie Payne Hubbard, Barbara Mason, Aubrey Barbour, Arthur Sales, and Betty Jean King, did so with love for the school, its students, and the community. Getting paid for doing so was just an added bonus, and we, as physical renditions of Yoder Memories, returned their love tenfold. Yoder School gave so much, as did all the people associated with it.

Somewhere in the annals of time, it seems the powers that be said to the naysayers of yore, “I will give them hope, an opening, a chance,” and placed Jacob Yoder's dream on the hearts of a city—“give them a gem, call it Yoder, and watch them shine,” and they (we) did.

The end? Maybe not. Today that same small building still occupies the space it has held since the 1960s. Admittedly, the outside and inside have been updated and renovated many times since 1971, but upon entering the Yoder Center, the spirit of Yoder School and the feelings of security it gave to the children of yore envelops you as if to say, “Welcome Home. I am still here.” How fortunate for the children that followed my generation to have still held a piece of Yoder, and their children that followed them to share in the memories of it. The original larger building is gone, but the spirit lives on in the dedication, service, and urgency of care in the people charged with the security and upkeep of the area today.

Beatrice Hunter, a retired Lynchburg native, has a passion for local Black history. She attended the beloved Yoder Elementary School in Tinbridge Hill, and has been published in Lynch's Ferry Magazine | A Journal of Lynchburg History - Memories, Fond and Painful, of Black Bottom. Bridge of Lament featured her writing last year in Day 13: What's in a Neighborhood? - Tinbridge Hill.

I love these sweet stories of founder and teachers. They paint a lovely mural of times past, flowing even into the future of an institution of incalculable worth to its community. It was conceived, built, and eventually modified to meet changing needs, and even today it still serves.

But the stories give life and depth to the real worth of the Yoder School, and its influence on the children it nourished and empowered are evident herein.

Many thanks to those who shared.

I always enjoying reading the work of Beatrice Hunter. Thank you, Beatrice, for keeping our history alive❤️