Day 7: Massive Resistance in Prince Edward County, 1959-1963

an interview with Phyllistine Mosley

While attending a centennial celebration for the Emancipation Proclamation on March 18, 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy said, “The only places on earth not to provide free public education are Communist China, North Vietnam, Sarawak, Singapore, British Honduras—and Prince Edward County, Virginia.”1

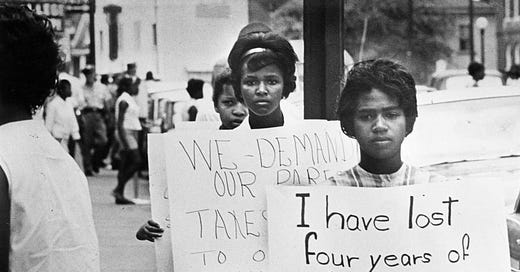

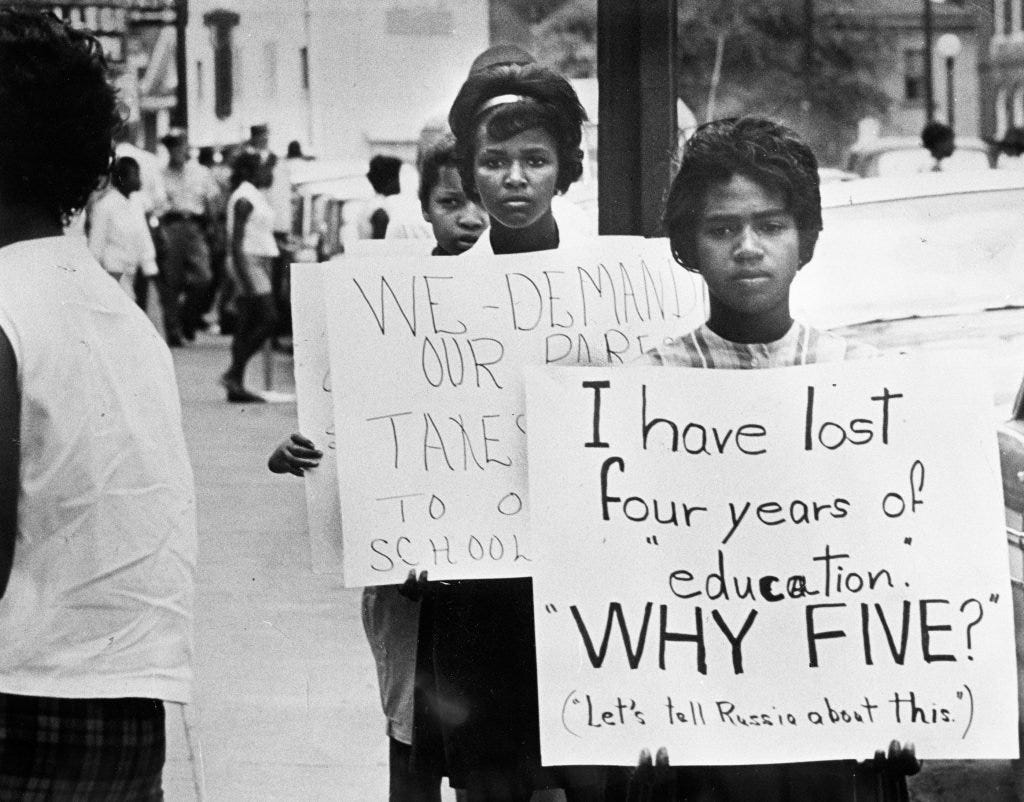

A fifty-minute drive east of Lynchburg brings you to the western edge of Prince Edward County. In 1959, the county and its largest town, Farmville, closed their schools in protest of the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs Board of Education ruling, which judged racial segregation unconstitutional. This protest, a state political movement in Virginia termed “Massive Resistance,” closed many schools across the state, including in Charlotteville, Front Royal, and Norfolk. Typically, these schools closed for two or three months and reopened after the Virginia Supreme Court declared Massive Resistance unconstitutional, also in 1959. But Prince Edward County was different. The County leaders believed that Blacks’ place in society was not to be in school with their white students. They chose not to reopen public schools, and the families of 2,500 Black students were left to fend for their education on their own for the next five years.2

One of these students, Philistine Ward Mosley, grew up in Farmville and attended the segregated R.R. Moton School. Mrs. Mosley has stewarded her community throughout her career and, in her retirement years, describes herself as a “Professional Volunteer.” Lynchburg’s Interfaith Outreach honored her in April this year for her exceptional service to the community. She serves on many local and state boards, including the Academy Center of the Arts, the Legacy Museum of African American History, and the Jubilee Center Family Development Center. In recent years, she has led the local Juneteenth Coalition, a group bringing song, dance, readings, history, and community service projects every Juneteenth for the last 25 years. I sat down recently with Mrs. Mosley to learn more about her personal story and what happened in Prince Edward County in the 1950s and 60s.

Martin: You grew up in Farmville, home of Longwood University, originally ‘Longwood Normal School,’ founded in 1839, which has since employed the past three generations of your family. Tell me more about your family story and how you came to grow up in Prince Edward County.

Mosley: On my father's side, Phillip Alexander Ward was my great-grandfather, born into enslavement in 1860. I knew Phillip because we lived with him until I was five years old, before we moved to our own home, but nothing was talked about regarding the history of our family and Longwood College. Later in life, at an ancestry program at the Farmville library, they had a Works Project Administration on the table, The Negro in Virginia. Thumbing through it, I came across, “Philip Ward, 84-year-old retired cook of Farmville State Teachers College, belonged to Charles Farmer of Jettersville Store.” Phillips' father Beverly had been enslaved on the plantation. The plantation house is still standing in Amelia County and is still very much intact and cared for by a curator. It’s likely Phillip stayed on the plantation for a number of years after the Civil War.

Sometime after the Civil War, Phillip left the plantation and moved to Farmville from Amelia County to work as a cook and baker at what was then known as Longwood Normal School. He had been a horseman on the plantation, but he learned how to cook and bake from my great-grandmother who was a cook in the plantation house.

We are three generations of Wards connected to Longwood University. Phillip Ward brought his son Charles in, and he cooked and baked, but my father, Philip Madison was just a baker who made fancy cakes and breads.

In 1934, the university gave my great-grandfather, Phillip, a 50-year certificate of service. They gave me my honorary Doctorate Degree in 2025, along with other students who were denied school in times past. It’s come full circle.

Martin: How did the white and Black kids interact in town during segregation? What about the parents?

Mosley: Neighborhoods were segregated. Growing up on Baptist Hill in Farmville, the type of Black neighborhood we lived in, we did not have any interactions with whites. My grandfather Charles had his own tobacco farm; my uncle had a general store. We lived on Main Street, where there was a school, a service station, restaurant, grocery store, beauty parlor, doctors’ office, and dentist's office—all the Black businesses we ever needed. My uncle’s store was on Ely Street, the next street over, which had beauty parlors, a funeral home, and master cleaners. Clothing would have been the only thing we needed to go downtown for.

If we went to the theater downtown, we would have to go to a side door and go upstairs. A lot of the time we didn’t go to the movies because of that. We played sports and went to the Prince Edward County Lake every summer where I learned how to swim, in the segregated Black section of the twin lakes.

Where we lived next door was a tourist home. She had a sign outside and was listed in the Greenbook, which shared all the places for Blacks to safely travel south to stay and eat. It was a normal home and inside she had lots of rooms, and she cooked and had a big dining area. We saw a lot of people travelling on Route 15 heading south.

On the other side of our house was a Teachery, where Black teachers came into Farmville to stay so they could teach. They stayed for the year to teach at the schools.

Martin: How important was the church to the Black community during this period?

Mosley: Very important. Historic First Baptist Church was the church I grew up in, where Reverend L. Francis Griffin was the pastor. He was a pastor and a Civil Rights leader. Reverend Dunlap, across the street, pastored the Methodist Church. Dunlap had a relationship with Kittrell Jr. College in North Carolina. He arranged for students from Prince Edward County to continue schooling when the schools closed.

Martin: Education was always important to Black families seeking better lives for their kids. What was life like in the Black schools before everything was closed?

Mosley: We had excellent teachers. You didn’t decide whether you would take a math class—you were going to take it, not choose to. They were going to teach you, and you were going to learn. The teachers encouraged you, and they worked with you until you got it. They exposed us to different programs and activities.

Dr. Dorothy Vaughn, from Hidden Figures, taught my husband math in fourth grade before going to Langley and working for NASA.

The County built our school, the original R.R. Moton School, originally for 180 students, but by my time, had enrolled over 400 there. It was a big auditorium with rooms around it. We didn’t have a cafeteria; we didn’t have any labs. They built three tar paper shacks for the overcrowding, heated with pot-bellied stoves. The kids had to start the fires.

After student Barbara Johns led the walkout strike in 19513 (precipitating Brown vs Board), they built us a new high school in 1954, taking the namesake R.R. Moton with it, the first public high school for Blacks in the community. It provided First Grade to Eleventh Grade. But we had hand-me-down books and equipment from the white school. The white Farmville High School was already there; they had everything, but they didn’t feel the need to change anything to accommodate us.

I played basketball, studied home economics, and went on to college to major in Home Ec. I loved art. My art teacher took us down to the Virginia State art show. Those were the types of exposures we had, encouraging us to be creative.

Martin: So what happened after they closed the schools?

Mosley: In 1959, we were still not equal to the whites. The County refused to integrate and thus decided to close the schools. Families worked together to make things happen for the kids. They met in church basements with teachers. Some parents put their kids in other counties' schools until the counties learned they were not from there and removed them. Many kids left the county to attend schools in other places.

Reverend Dunlop from the Methodist church arranged for 60 students from Prince Edward County to continue schooling at Kittrell Jr. College in North Carolina. They prioritized giving seniors their last year of high school, but as there was room for some juniors to attend too, I came along as well. My brother was a senior at Kittrell that year, I was a junior. We lived in a dorm in our own area of campus. Can you imagine being a high schooler and making independent decisions that normally are made shared with your parents?

We didn’t really interact with the college kids, although we ate together in the cafeteria. They did their best to give us a normal high school experience, with a football team and a prom.

For my senior year, I went west to Yellow Springs, Ohio, and lived with a Quaker family. There was a program run by the American Friends Service Committee that saw what was happening in Prince Edward County and stepped in to place dozens of students in homes where they would receive a good education. I was used to traveling with our family growing up, and I wanted the experience of this program.

Schools remained closed for five years, until 1964 when Attorney General Robert Kennedy opened free schools for Blacks, and then the public schools reopened after Reverend Griffen, the Civil Rights leader from Farmville, went to court and sued the state of Virginia. When schools opened back up, Blacks went back to their same newer Moton High School, which at that point reopened for both Black and white students.

Martin: Thank you for your time. What are a few words of encouragement you have for people concerned about the education of our students today?

Mosley: Too many students today are not curious, they are not inquisitive, they have no idea about anything other than the device they have in front of them. We need to get kids interested in what's around them and what they are exposed to, let them internalize it, and realize if it is something they want to do.

The Jubilee Center in Lynchburg does great work. They expose kids to so much. They encourage them to do their homework. They encourage interest in different things. They take them to places. The Boys and Girls Club also creates a good atmosphere to be curious about different jobs and opportunities, and careers, and to learn skills.

Encourage students to be inquisitive. Be curious. Seek out things they are interested in and learn from it.

Phyllistine Mosley honored me with her time for this interview. She is a servant of the community and an inspiration to those of us who care for that community. She left me with a closing thought that sticks with me as we see our history being taken down from government facilities and websites in our current political climate. “Juneteenth is history. I know the plantation where my ancestors were enslaved. I have been to the building; I have walked the grounds. You cannot take that away from me.” Learn more about Mrs. Mosley in ABC13’s Recognizing Phyllistine Mosley Women's History Month.

Poor whites were impacted too. While wealthy white students could attend a newly opened Academy in Farmville to continue their education, the poor white students were left without schooling.

One of the five cases combined in Brown v. Board was Dorthy E Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County. A student-led strike in 1951 initiated the suit. Barbara Johns was fed up with the poor conditions at the town’s only Black school and organized a walkout. Johns was a niece of Vernon Johns from Virginia who pastored First Baptist Church, was president for a term at Virginia Seminary of Lynchburg, and later was Dr Martin Luther King’s predecessor at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta.

Wow. Such an impactful story—thank you for sharing!!