Day 8: Jubal Early and the Lost Cause

Eight days across the Bridge of Lament, buoyed by Black joy in our weekend’s readings, we face the headwinds of another week in returning to the Confederacy and Jubal Early.

Editor’s Note: In Friday’s excerpts from Harry S. Ferguson, we shared an 1884 quote from the Lynchburg News: “If you are white, stay white, for the Anglo-Saxon who forgets his race, blood, and proud heritage and bands with the Negroes deserves unspeakable scorn and the whip of scorpions.” Over the next two days, we will share how Early’s legacy inspired these comments, contributed to the rise of Jim Crow, and fueled the political disenfranchisement of African Americans across the South for seventy-five years.

The trick with the trains was not Jubal Early’s most damaging or damning ruse. Winning the Battle of Lynchburg helped preserve the South’s slave republic for another year. But winning the propaganda battle with the myth of “the Lost Cause” has fueled white supremacist memory and understanding for generations, into our own time. Two men more than any others are responsible for the Lost Cause myth: Confederate president Jefferson Davis and the man valorized by my neighborhood, Jubal Early.

I realize that is a hard claim—one that may cause skeptical readers to balk, to think I’m overstating things, or maybe to object that I’m judging the past in modern terms. I want to dialogue with that skepticism. Allow me to work through this claim one step at a time and argue these three points:

The Confederate States of America (CSA) was formed explicitly as a white supremacist slave republic.

The CSA fought the Civil War to preserve white supremacy and perpetuate enslavement.

The Lost Cause Myth successfully recast the nature and aims of the Confederacy in ways that still influence our thinking today.

That argument requires an in-depth look at historical documents, so we will break it over two days. Today we will examine the first two claims, and tomorrow we’ll tackle the third.

1. The CSA was formed as a white supremacist slave republic.

The phrase “slave republic” is not a modern viewpoint imposed on the past. It is what Confederates themselves said about the republic they were forming as they formed it.

In February of 1861, L. W. Spratt wrote an essay beckoning other slaveholding states to join South Carolina in secession. He opened his essay with these words: “The South is now in the formation of a Slave Republic” (italics in original).1 To avoid any confusion about the Confederacy’s motives, he dismissed other potential causes:

The contest is not between the North and South as geographical sections . . . nor between the people of the North and the people of the South, for our relations have been pleasant . . . But the real contest is between the two forms of society which have become established, the one at the North and the other at the South. . . .

The one is a society composed of one race, the other of two races. The one is bound together but by the two great social relations of husband and wife and parent and child; the other by the three relations of husband and wife, and parent and child, and master and slave. The one embodies in its political structure the principle that equality is the right of man; the other that it is the right of equals only.2 (Italics in original.)

Lynchburg resident William Holcombe agreed in his own February 1861 essay in favor of joining the Confederacy:

He has not analyzed this subject aright . . . who supposes that the real quarrel between the North and the South is about the Territories, or the decision of the Supreme Court, or even the Constitution itself . . . The true secret of it lies in the total reversion of public opinion which has occurred in both sections of the country in the last quarter of a century on the subject of slavery. . . .

In opposition to the prevailing sentiment of the North, we believe that men are created neither free nor equal. They are born unequal in physical and mental endowments, and no possible circumstances or culture could ever raise the negro race to any genuine equality with the white. . . . That government is the best, and its people the happiest, not in which all are free and equal, but in which equal races are free, and the inferior race is wisely and humanely subordinated. . . .The only hope of the African is in his just subordination to the superior type.3

In short, Spratt, Holcombe, and myriad other Confederates plainly say that the society they were creating, because they thought it was the best form of society, was a slave republic where “the superior race” would rule. It may be a hard truth to accept, but it is true: the CSA was formed explicitly as a white supremacist slave republic.

2. The CSA fought the Civil War to preserve white supremacy and perpetuate enslavement.

Once you know that Confederates believed a white supremacist slave republic was the ideal form of government, it makes sense that they would kill and die to defend it. The objection is often raised, however, that only a minority of white Southerners were slaveholders, so how could the average soldier have been fighting to protect slavery?

The question misunderstands both history and soldiers’ motivations. The average American soldier in, for example, the Gulf War did not fight because they had shares in an oil company. Their individual motives varied widely. Some fought for a flag, an idea, a way of life. Some fought for the social benefits of being a soldier (e.g., money for education, or respect in civilian life). Some fought simply because they were ordered to. All fought to defend men and women who had become brothers and sisters to them. Nevertheless, the Gulf War was explicitly conducted to protect American strategic oil interests in Kuwait.

The Southern situation in 1860 was similar. Individual soldiers joined for a variety of reasons,4 not necessarily from personal conviction to preserve enslavement. But we cannot overlook that white supremacy and Black enslavement was “the Southern way of life” and the South’s “peculiar institution.” It touched the lives of every person: plantation owners, small farmers who leased slaves, middle class households that enslaved a single “house servant,” free Black men and women, enslaved persons themselves, and Native Americans trying to navigate white society’s perpetual negotiation of their place in a racial hierarchy. The motives of each Confederate soldier would vary widely, just as the motives of each modern soldier does, but a great many were willing to fight for a way of life built around white supremacy and paid for by Black enslavement. And regardless of Confederate soldiers’ individual motives, the Civil War was explicitly conducted to protect Southern interests in human “property.”

We have already looked at pro-secession pamphlets where Confederates say as much. But we can see the same point in the “declaration of causes” documents the Southern states wrote to explain why they were leaving the United States and joining the Confederacy:

South Carolina left immediately after the 1860 election because the victorious party held “opinions and purposes [that] are hostile to slavery.”5

Mississippi opened its secession act by declaring, “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery.”

Georgia complained, “For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery.”

The official acts of secession are clear: the central issue that the Confederacy was formed to protect, by force of arms if needed, was slavery.

Similarly, look at the constitution that the Confederacy established and fought to defend. It is in many ways identical to the U. S. Constitution, but has several key additions:

“No . . . law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.” (Art I, Sec 9, Clause 4)

and

“The Confederate States may acquire new territory …In all such territory the institution of negro slavery …shall be recognized and protected.” (Art IV, Sec 3, Clause 3)

Tellingly, the Confederate Constitution did not establish states’ rights on the question of slavery. They did not say that states rather than the federal government should be able to decide matters. No, their central government tolerated no dissent on the question that mattered most to them: all Confederate states must be slave states, and no law can be passed against slavery.

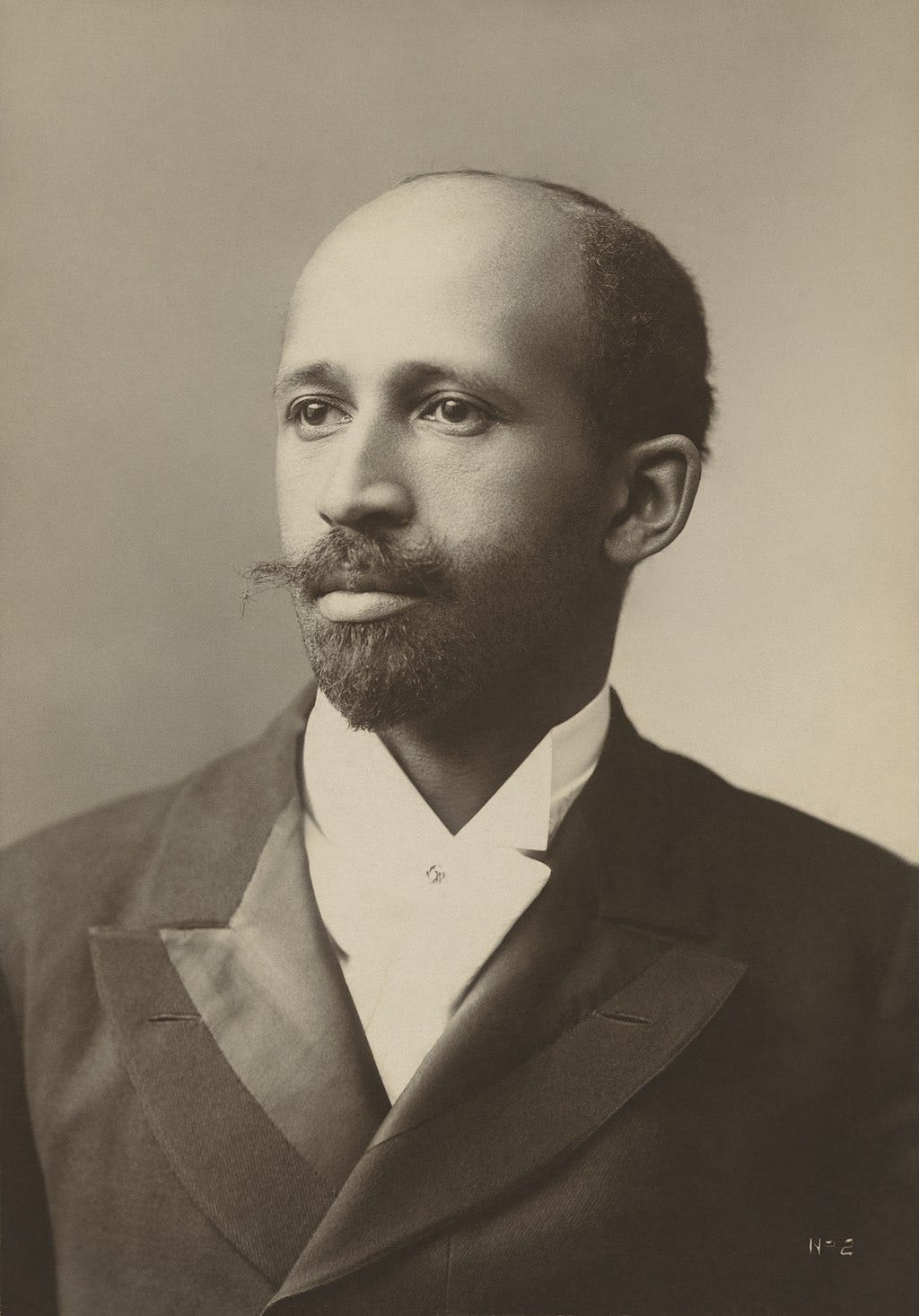

The most important and insightful critic of the Lost Cause myth, W. E. B. Du Bois, understood the “States’ Rights” argument perfectly:

“The South cared only for State Rights as a weapon to defend slavery. If nationalism had been a stronger defense of the slave system than particularism, the South would have been as nationalist in 1861 as it had been in 1812.”6

Celebrating the ratification of this Confederate Constitution, the Vice President of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens, infamously boasted,

The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution—African slavery as it exists amongst us—the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.”

Stephens crowed that the Confederacy was superior to the United States because the U.S. Founders believed that slavery was wrong and would eventually be eradicated. Here is his response:

Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government built upon it fell when the "storm came and the wind blew.” Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. [Applause]7

(“Applause,” the transcripts note, calling to mind once again Jubal Early’s empty train. There’s nothing inside, it’s all a pretense at strength that isn’t there, but people are expected to cheer riotously so everyone keeps believing the lie.)

The historical evidence is overwhelming. In their own words, the Confederacy was formed as an explicitly white supremacist slave republic. The Civil War was fought to preserve White power and perpetuate Black enslavement. They said so, over and over again.

If the historical record is clear, why is it that so many Americans believe the Civil War was about something other than slavery? That critical question leads to my third point about Jubal Early’s more lasting ruse, the Lost Cause Myth. That is the subject of tomorrow’s post.

Questions or feedback? We’d love to hear from you. Email bridgeoflament@gmail.com.

L. W. Spratt, “The Philosophy of Secession: A Southern View.” February 1861. https://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/secession/secession.html

Ibid.

William Holcombe, “The Alternative: A Separate Nationalist, or the Africanization of the South.” https://civilwarcauses.org/holcombe.htm

It should be noted, though, that many didn’t join. There were movements across the South, particularly among poor whites, to resist conscription and to flee from forced service at the first opportunity. The 2016 film The Free State of Jones is a fictionalization of the real story of Newton Knight, who led one such effort.

“The Declaration of Causes of Seceding States: Primary Sources,” American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/declaration-causes-seceding-states

W. E. B. Du Bois, “Robert E. Lee,” The Crisis v. 35. March 1928.

Alexander Stephens, “Cornerstone Speech.” https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/cornerstone-speech-by-alexander-h-stephens-march-21-1861/