Day 9: Jubal Early and the Lost Cause, continued

If the historical record is clear, why do so many Americans believe the Civil War was about something other than slavery?

Last Thursday, I wrote about how Lynchburg memorializes Jubal Early for the ruse he used to win the Battle of Lynchburg. Yesterday, I began the argument that Early’s far more damaging ruse was the Lost Cause Myth, which has taught generations of Americans comfortable lies (comfortable for white people, anyway) about slavery and the Civil War. I ended yesterday’s post with this question: If the historical record is so clear, why do so many Americans believe the Civil War was about something other than slavery?

To answer that question, I want to return to the third point in yesterday’s essay, and consider the contribution of the man honored in my neighborhood: Jubal Early.

3. The Myth of the Lost Cause recast the Confederacy in ways that still influence our thinking today.

The Lost Cause is not simply a historical error. It has implications for how people think about American history and how it should be taught, but also about the social issues facing many Black communities. It affects how people speak about their neighbors and fellow citizens.

Following the Confederate surrender at the end of the Civil War, Early fled to Mexico. Only after President Andrew Johnson pardoned all Confederate officers did he return, settling in Lynchburg, and proudly declaring himself “an unreconstructed rebel.” As his personal life increasingly fell to shambles and squalor, he grew more bitter and resentful.1 Early needed to counteract his personal and military defeats. He needed to remember the past differently.

So Early undertook a writing campaign to retell the story of the Confederacy.

First in a book about his own experience of the war, and then as president of the Southern Historical Society, Early crafted the soothing lies that the Civil War was fought to preserve liberty and states’ rights against a tyrannical government, that the South lost because it insisted on fighting with honor, and that slavery was a benevolent institution where White enslavers treated with fatherly care the men, women, and children they held in bondage, who were not ready yet for the burdens of self-government.

Are those lies familiar? They are to me. I was taught them growing up. I saw them just this week on social media. I’ve taught alongside adults who taught them to my students. These are the central elements of the Lost Cause Myth.

This matters, because the Lost Cause is not simply a historical error. Language shapes our memory, and memory shapes our understanding. The Lost Cause has implications for how people today think about American history and how it should be taught, but also about the social issues facing many Black communities. It affects how people speak about their neighbors and fellow citizens. White supremacy and Black infantilization2 were and are central to the Lost Cause view. Jubal Early knew this. In his 1866 book inaugurating the Lost Cause, he wrote:

The Creator of the Universe had stamped [Black Americans], indelibly, with a different color and an inferior physical and mental organization. …Reason, common sense, true humanity to the black, as well as the safety of the white race, required that the inferior race should be kept in a state of subordination. The conditions of domestic slavery, as it existed in the South, had not only resulted in a great improvement in the moral and physical condition of the negro race, but had furnished a class of laborers as happy and contented as any in the world.3

The wounded White South ate it up hungrily. To lose an enslaver’s rebellion is a shameful thing; to lose a trial of honor in defense of liberty and “the natural order” because you would not stoop feels much finer. W. E. B. Du Bois astutely observed:

In the South, particularly, human ingenuity has been put to it to explain on its war monuments, the Confederacy. Of course, the plain truth of the matter would be an inscription something like this: “Sacred to the memory of those who fought to Perpetuate Human Slavery.” But that reads with increasing difficulty as time goes on. It does, however, seem to be overdoing the matter to read on a North Carolina Confederate monument: “Died Fighting for Liberty!”4

In time, the White North accepted it, too, as the face-saving cost of reunification: let White Southerners memorialize the war as the doomed but noble struggle of a chivalrous agrarian society against a powerful industrial society—the inevitable but romantic passing of an older way of life—and the country can reunify and move on. But as Henry Louis Gate, Jr. masterfully argues in Stony the Road, the cost of that lie was the progress made by Black Southerners during Reconstruction. The cost of that lie was 100 years of Jim Crow. For the Lost Cause Myth to be true, Black people had to be better suited to slavery and incapable of self-government. White rule had to be accepted as the natural order, and best for everyone.

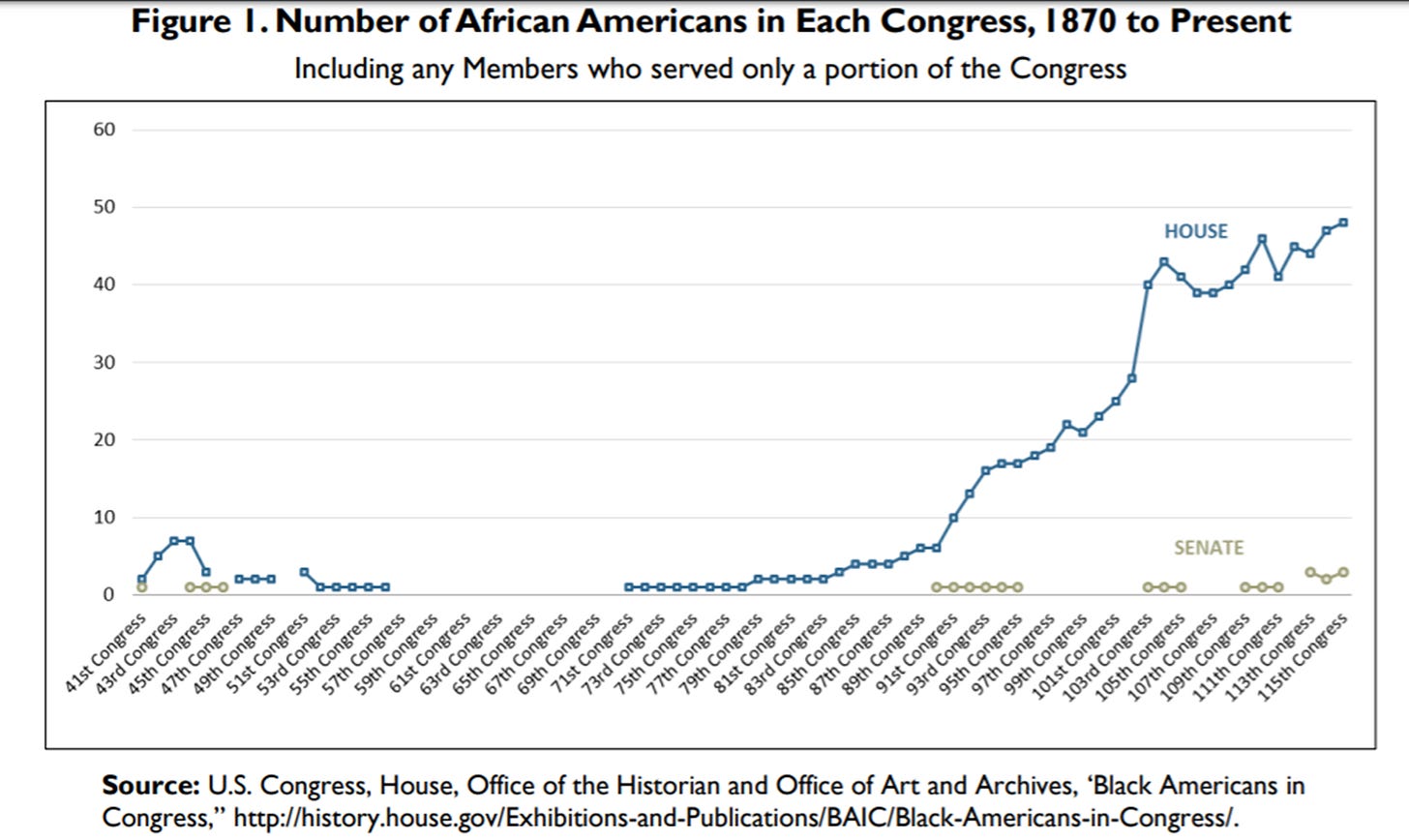

White America bought the lie, and the gains in business, community, and politics that Black Southerners had made during Reconstruction were violently grabbed back. In the years immediately after the Civil War, hundreds of thousands of Black voters elected sixteen Black U.S. Congressmen, two Black U.S. Senators, and over 1,500 Black representatives in state and local offices. This number includes five Black men elected to Lynchburg’s city council.

But after twenty years of Lost Cause mythology and the white supremacist terror that accompanied it, Black Americans were murdered, terrorized, and then barred from voting by poll taxes and voting tests. The Black vote evaporated in the span of a decade, as “every state in the Deep South adopted a new state constitution, explicitly for the purpose of disenfranchising blacks.”5 Virginia did as well: a new 1902 constitution was written by Lynchburg native Carter Glass specifically to deprive Black Virginians of the vote.

The result? It would be another 100 years before there were as many Black representatives in the U.S. Congress as there had been in 1875.

But the legacy of the Lost Cause did not end with the restoration of Black voting rights in 1965. Our nation today still falls for Jubal Early’s ruse. Despite the overwhelming historical evidence and the near-unanimity of historians, a 2011 poll found that half of the American public believed states’ rights was the main cause of the Civil War, while only 38% believed it was slavery.6

And remember, the Lost Cause is not a merely historical error. It is white supremacist mythology that depends on two central ideas: that White Rule was (and is) beneficent, and that Black people are culturally inferior. Those poisonous vines have deep roots, and they are thriving. A person who believes in the Lost Cause is primed to believe, for example, that racial disparities in social outcomes (e.g., home ownership rates or median family wealth) are “their own fault” because despite being given every chance by a beneficent white society, Black people’s inferior culture holds them back.

Friends, that is the same viewpoint that Jubal Early penned in 1866. It’s the same white supremacist ruse, the same empty train. But remember this: the ruse only works if you keep cheering.

I lament that this vicious man, who has done incalculable damage to our nation’s peace and its soul, is valorized by our city. By my neighborhood. By the monument one block from my house. Instead of memorializing a bitter white supremacist and chief architect of one of our nations’ most damaging lies, we should instead memorialize the Black Lynchburgers who resisted enslavement, or the Lynchburg Quakers who spoke out against it, or abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and David Hunter who fought for the equality of all people. We should begin by educating ourselves—by unlearning the Lost Cause lies that Jubal Early taught us.7

Questions or feedback? We’d love to hear from you. Email bridgeoflament@gmail.com.

See, for example, descriptions by his visitors in Martin F. Schmitt, “An Interview with General Jubal A. Early in 1889,” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 11, num. 4 (Nov. 1945), pgs 547-563. https://doi.org/10.2307/2198313

Infantilization” is treating someone, or in this case a group of people, as though they were children.

Jubal Early, A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence in the Confederate States of America. 1866. Page ix. https://www.loc.gov/item/02017136/

W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Perfect Vacation,” The Crisis, 1931.

A good way to do this is to learn from Black scholars. W. E. B. Du Bois and Ida B. Wells are historical figures to read, and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Nell Irvin Painter are contemporary scholars who lead the field.