Day 9: The History of Lynchburg's Confederate Monument

I strongly believe that the statue should be removed. To make that case, I want to contextualize Lynchburg’s Confederate Monument

As I write this, it is the first Sunday after Easter, known in some Christian traditions as Divine Mercy Sunday. On this Sunday, Christians who follow the lectionary—around the world and across generations—read in the book of Acts about the early Christians being “of one heart and soul” and holding everything in common. We recite from Psalm 133, “how good and pleasant it is when kindred dwell together in unity.”

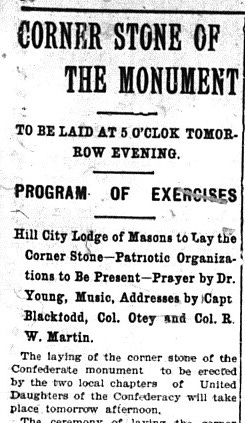

124 years ago, Divine Mercy Sunday fell on April 22, 1900. That morning, many of Lynchburg’s churches would have read those same passages about unity and community. That same afternoon, those churchgoers would have read in Lynchburg’s paper, The News, about the celebration planned for the installation of a Confederate monument in front of the Lynchburg courthouse.

124 years later, our nation is debating what to do with monuments to the Confederacy. Some say we should take them down because they are celebrations of white supremacy. Some insist they should remain because they are part of our history. Others adopt middle ground positions, wanting the statues to stand but be contextualized with additional information. And of course there are the extremists, like those who marched in Charlottesville in 2017, who agree the statues are monuments to white supremacy and violently defend them on precisely those grounds.

This debate is happening in Lynchburg, as well. In December 2021, the city’s African American Cultural Committee submitted a report to the City Council on ways to honor the contributions of Black Lynchburgers. The committee was divided on the Confederate monument. Some members “felt strongly that the statue should be replaced with a more inclusive monument or symbol” and argued for moving it into the Lynchburg Museum.1 But others “felt its replacement would simply be symbolic and would not achieve anything of lasting substance.”2 Unable to reach consensus, the committee made no recommendation about the statue.

I strongly believe that the statue should be removed. To make that case, I would like to do something the statue’s defenders call for: I want to contextualize Lynchburg’s Confederate Monument. Once the monument’s context is better understood, I believe the case for removing it or relocating it into the museum is clear.

Historical Context

The April 22, 1900 article from The News details the ceremony white Lynchburgers had planned for the installation of the city’s Confederate monument on April 23. Let’s not miss this point: In 1900, roughly half of Lynchburg’s population was Black.3 They are not represented in the events of the day. The pastors and poets listed in the article were white. All of the historical figures they honored were white.

This is no mere accident or oversight. It is an intentional exclusion. It’s a message.

As we wrote about in “Five Years of Equal Representation,” from 1885 to 1889, five of Lynchburg’s city council members were African-American, and in 1898 a Black man named Daniel Butler was the 6th District’s Republican nominee to Congress. In that period of Black representation, this same Lynchburg paper, The News, opined, “the Anglo-Saxon who forgets his race, blood, and proud heritage and bands with the Negroes deserves unspeakable scorn and the whip of scorpions.” Following Butler’s defeat, Virginia—like all the Southern states—rewrote its Constitution specifically to disenfranchise Black voters. This effort was led by Lynchburg native Carter Glass.

In other words, 1900 fell right in the middle of a vicious white backlash against Black representation in local and national politics. No one in that crowd would have been unaware of those facts, any more than you or I are unaware of our own day’s most heated political issues. That entire white crowd would have been aware of their immediate political context, which is: Shortly after Lynchburg’s Black councilmembers were removed, and while Virginia’s constitution was being rewritten to ensure no more Black representatives were elected, a white crowd placed a memorial to the Confederacy and its cause in the city’s most prominent location.

This statue was an act of defiant “redemption”—the term that white southerners of that period used for rolling back the political gains Black southerners made immediately after the Civil War and re-establishing white rule.

But we do not need to rely on the monument’s timing alone to see that. The speakers on that April day made clear that their memorial was an attempt to perpetuate the Confederate cause to future generations.

Above all things, let the generations of the future remember that [the Confederate soldier] fought not for what he thought was right, but what he knew was right. Upon the efforts of the present the people of the South should build a future that would reflect the glory of the Confederacy and the cause for which her people fought and suffered.4

The cause that Confederates fought for, what they “knew was right,” was—in their own words—“a Slave Republic” where “the inferior race [sic] is wisely and humanely subordinated.” (That last phrase was penned by Lynchburg’s own Willliam H. Holcombe.) When white folks in 1900 defiantly asserted that the Confederate cause was right, they meant a society under white rule that kept Black people controlled and out of power was the right kind of society.

The tokens of remembrance that white crowd brought tell the same story. The April 22 article lists more than two dozen mementos that the white populace had gathered to place in the statue’s base. Each tells a story about the monument’s context—about what it meant to the people gathered to erect it. Here are some of those mementos:5

Picture of General Jubal A. Early

“Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence,” by General Early

Clipping from The News describing General Early’s monument

We talked last year about the legacy of Jubal Early and his monument. His book, Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence, is the revisionist history that launched the Lost Cause. Central to the Lost Cause mythology was the white supremacist lie that Black Americans were intellectually inferior, so it was right that they be controlled by white rule. As Early wrote in that very book that white Lynchburgers reverently placed in the Confederate Monument’s base: “Reason, common sense, true humanity to the black, as well as the safety of the white race, required that the inferior race [sic] should be kept in a state of subordination.”6 Those hateful words are still there today, ensconced in the foundation of Lynchburg’s most prominent statue.

There is another pillar of Lost Cause mythology included in the statue’s base:

Portrait of Mrs. C. J. M. Jordan and a poem by her

Though the article does not name the poem, given the occasion, it is very likely the one that made the Lynchburg native Cornelia J. M. Jordan famous: “Richmond: her Glory and her Graves.” This 1867 elegy portrayed Confederate soldiers as holy martyrs who died in a righteous and just cause. With deep but unconscious irony, the poem calls for God to avenge the oppressed. Jordan does not mean the millions of Black men and women that had been held in bondage, but the humiliated Confederacy. It ends with the line, “Immortal Truth must still prevail; God will defend the Right!”

Again, when white southerners in 1900 talked about the righteousness, justice, or obvious truth of the Confederate cause, they were referring to their current political cause: “Redemption.” And as the name implies, white southerners in 1900 saw their current political cause as “redeeming”—winning back—the kind of government the Confederacy fought for: White rule and Black subjugation.

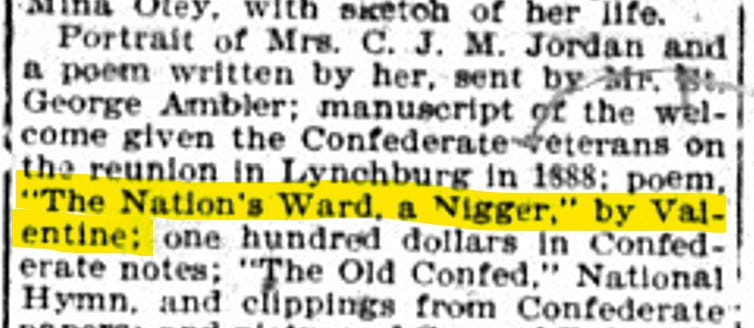

Let us examine one final memento — one last context clue that helps us see what the Confederate statue meant to the white residents who put it up. A second poem was laid in the statue’s base at the place of highest honor in our city. Here again is the article in The News:

I believe The News is in error here. I have found no poem called “The Nation’s Ward, a N***r” by a poet named Valentine. There is, however, a sculpture titled The Nation’s Ward done by the famous Virginia sculptor, Edward Valentine, completed some time in the 1870s.

Valentine’s most famous work is the recumbent Robert E. Lee that lies atop Lee’s sarcophagus in Lexington, so he was certainly an artist who knew how to capture dignity. However, he did not bring that viewpoint to The Nation’s Ward. Instead, Valentine created a racist caricature of a smiling Black boy, looking up at the viewer with good-natured anticipation.7

The title The Nation’s Ward echoes the old Lost Cause theme that Black Americans are the wards—the surrogate children—of white people. The white supremacist mythology of the Lost Cause insisted that Black citizens were not ready for the burdens of citizenship. Instead it portrayed them as childlike, simple, in need of wiser supervision. This view, like the old pro-slavery lie it evolved from, imagined white citizens as parental figures who would (supposedly) take care of a people they saw and treated as inferior. That is the ideology behind the phrase, “The Nation’s Ward”

So how does The Nation’s Ward, a sculpture by Edward Valentine, become “poem, ‘The Nation’s Ward, a N****r,’ by Valentine” in the news article?

I suspect the memento placed in our statue’s base is an ekphrastic poem: a poem that meditates on an object of art and describes what the object makes the poet think or feel.8 Some poet whose name has been lost to history meditated on Valentine’s racist sculpture and wrote a poem about the thoughts and feelings that subservient face inspired. They titled their poetic reflection, “The Nation’s Ward, a N****r, by Valentine.” The reporter, seeing or hearing that title in a list of objects being placed in the Confederate memorial, mistook the last two words of the title for the poet’s name.

We don’t have the full text of the poem to show us exactly what those thoughts and feelings were, but the poet adding the racial slur to Valentine’s already demeaning title certainly gives us a clue. This poem is likely a white Lynchburger insisting their Black neighbors are not “ready for” elected positions and voting rights and insisting that only white people can be trusted to decide what’s best for their Black neighbors.

(It’s a very convenient lie for a crowd well aware that they’ve just ousted all the city’s Black councilmembers and are rewriting the state constitution to keep Black Virginians from voting for another 65 years.)

And the poet added to that convenient white lie the massive weight of disdain, dismissal, and hatred behind the ugliest racial slur.

This poem—all these mementos—like the word placed under a statue’s tongue to animate a golem—tells us what spirit and purpose the statue held in the eyes of the people who erected it.

Certainly the monument was also a memorial to the white Lynchburgers who had died in the Civil War, but those two causes are inextricably linked. What Lynchburg’s Confederate monument meant to those who put it up in 1900 was this: we remember the cause our ancestors fought for and celebrate that we’ve achieved it. The monument celebrates that white rule had been re-established in Lynchburg.

That is the context. I trust we can agree that sentiment is not one that our city ought to publicly honor and celebrate. Tomorrow, we will look at how a monument erected in honor of white supremacy is not just a historical problem, but a present-day problem for our city, too.

“Report of the African American Cultural Committee,” December 14, 2021, https://lynchburg.granicus.com/MetaViewer.php?view_id=4&event_id=534&meta_id=49501, 16.

Ibid.

Lynchburg Museum, “Hill City Roots: A Guide to Black History in Lynchburg, Virginia,” https://www.lynchburgmuseum.org/hill-city-roots.

Major Peter J. Otey, quoted in “In Honor of the Soldiers: Corner Stone of Confederate Monument Laid,” The News, April 24, 1900.

A fuller list can be seen in the April 22, 1900 edition of The News, and on pages 172-174 of Philip Lightfoot Scruggs, The History of Lynchburg Virginia, 1786-1946, J. P. Bell Co., Inc.

Jubal Early, A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence in the Confederate States of America. 1866. Page ix. https://www.loc.gov/item/02017136/

If you suspect I’m misjudging Valentine, I invite you to look at his other statues of Black figures. Note the sneering irony he uses in a title like Knowledge is Power for a statue of a Black boy who’s fallen asleep over a book.

For example, John Keats’ poem “Ode on a Grecian Urn” records the poet’s thoughts on time, truth, and beauty as he looks at a piece of ancient pottery in a museum.

And just to note--a statue of a soldier with a bayonet deployed, in front of what is supposed to be a place of justice (courthouse), does not seem to be an appropriate message.

Thank you for providing this beautifully written context for the statue, and likely many other similar statues throughout the south. The statue should be removed, but the historical context not lost. Losing the context would be burying history. Perhaps moving it to the (or a) museum, but only as part of an exhibit that explains its origins and what it was doing in Lynchburg.