For the three Wednesdays leading up to this year’s bridge crossing, we are sharing essays from the 2023 archives. This essay by Jeremiah Forshey considers local lore and recorded history surrounding Civil War events in our city, continuing the idea from last Wednesday’s post that “We can choose how we tell the stories about our past. We choose what to dignify and memorialize.” (Look for another historical research piece from Jeremiah this year, on Lynchburg’s Confederate monument.)

I live in Lynchburg’s Fort Hill neighborhood, named for the Civil War fortification that sits one block from my house. Wrought iron gates label the place “Fort Early,” and a seventeen-foot granite obelisk, a miniature Washington Monument, honors the Confederate officer for whom the fort is named: Jubal Early.

The history behind this place, its monuments, and that man tells a story about how memory gives shape to our understanding of the past, and how the stories white supremacy has told continue to affect our present.

“Fort” is a generous name bestowed by memory. A visitor might think the brick wall, low square building, and iron gates are the fort, but that’s not right. The original defenses were a modest earthwork redoubt hastily dug on the afternoon of June 17, 1864. Confederate soldiers under the command of Jubal Early piled dirt twelve feet high, preparing to stop Union General David Hunter from reaching Lynchburg’s vital rail hub. That hub was central to moving Confederate troops and supplies through “the Southern slaveholding States” (to use the words of Virginia’s Ordinance of Secession).

The Battle of Lynchburg lasted two days and was won by a clever ruse. Early had a single empty train running in and out of Lynchburg, and the people of Lynchburg were instructed to wait by the station and cheer riotously whenever the empty train pulled in. Hearing the train and the cheers, Hunter’s scouts believed that Early was being continually reinforced. Hunter feared he was outnumbered and was running low on ammunition after several skirmishes. He retreated, and Early was hailed as “the Savior of Lynchburg.”1

That’s the story we’re told. But if we examine the way that story is told, who it centers and who it forgets, a different picture emerges.

In the 1860 census, Lynchburg had roughly 6,800 residents, 3,800 White and 3,000 Black.2 In other words, the population was split roughly in half along racial lines. When the history texts say that “the people of Lynchburg” cheered at the arrival of Early’s empty trains, which residents were cheering? When Early was hailed as “the Savior of Lynchburg,” who exactly was being saved?

These aren’t just idle questions. We as a city have chosen to remember and tell the story of one half of the population as though it were the story of Lynchburg. We have chosen to simply ignore another half of our city as though they didn’t exist. That is white supremacy in action. What story might a Black Lynchburger tell about that summer night in 1864, hearing the White populace cheer at the empty trains, hearing that the Union was just outside the city?

Union General David Hunter had a reputation. Months before Frederick Douglass saved the Union by convincing President Lincoln that Black men could be trusted to take up arms in their own defense, David Hunter already believed it. In the spring of 1862, he formed the first Black Regiment in American history. Union leadership, fearing political blowback, ordered him to disband it. Hunter refused with anti-racist flair. He wrote to Congress,

“I reply that no regiment of ‘Fugitive Slaves’ has been, or is being organized in this Department. There is, however, a fine regiment of persons whose late masters are ‘Fugitive Rebels’ … [T]he loyal persons composing this regiment … are now, one and all, working with remarkable industry to … go in full and effective pursuit of their fugacious and traitorous proprietors.”

Similarly, eight months before Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, Hunter issued General Order 11 in the theater he commanded, declaring “the persons in these three States—Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina—heretofore held as slaves, are … declared forever free.”

Hunter’s language matters, because language shapes our memory and our understanding. These men are not fugitive slaves, Hunter insists. They are persons who had been held as slaves, but are defined by (and should be remembered for) their loyalty, industry, courage, and valor.

This distinction was important in the 1860s: Douglass had to work tirelessly and use all his considerable rhetorical power because most White Americans (including northerners and Lincoln himself) were convinced that Black Americans were “natural slaves” and lacked the noble characteristics necessary to be good soldiers.

It is equally important today: when remembering and retelling the story of our nation’s long struggle for equality, we must reject the white supremacist lie that Black Americans were passive recipients of that struggle. We must remember and retell the ways they led the fight for our nation’s soul.

Lamentably, this is the way our city remembers the battle:

In the 1920s, the nation was gripped by White backlash to Black advancement made during Reconstruction. This was an era that saw the resurgence of the KKK, a spike in lynchings and other racial terrorism, the adoption of the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of white supremacy, a spate of books and articles hand-wringing that civilization would collapse as Whites were being out-populated,3 and hundreds of memorials valorizing the Confederate cause.

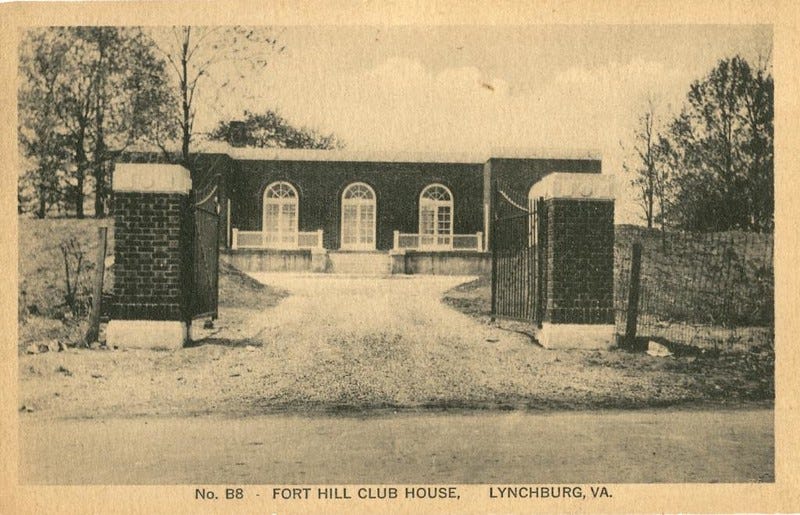

It was during this decade that the Daughters of the Confederacy cleaned up Lynchburg’s overgrown earthworks, built the brick wall and building, installed the iron gates, and erected the obelisk---turning the site into a “perpetual memorial to the officers and soldiers of the Confederate army.”4

In keeping with the spirit of Juneteenth, our project seeks to build a bridge from lament over the legacy of white supremacy to celebration of Black freedom. We can choose how we tell the stories about our past. We choose what to dignify and memorialize.

We should not accept the story white supremacy crafted in the 1920s about a battle to preserve the power of one half of Lynchburg’s residents, in order to hold the other half in bondage. White supremacy is still running the same empty train into our city again and again, pretending to a strength it does not have, asking us to cheer to maintain the ruse.

We can refuse.

Martin F. Schmitt, “An Interview with General Jubal A. Early in 1889,” The Journal of Southern History, vol 11, num 4 (Nov 1945), pg 555.. https://doi.org/10.2307/2198313

http://www.thomaslegion.net/battleoflynchburg.html

See, for example, Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color: The Threat Against White World Supremacy, 1920.

U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Servce, “National Register of Historic Places: Registration Form,” https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/118-5162_Fort_Early&Jubal_Early_Monument_2002_Final_Nomination.pdf