Lynchburg Votes!

"The fact that the Negro had now reached the stage where he could have a voice in the actual operation of the city’s government...inspired a new political zeal in him"

In 2023, Bridge of Lament shared the history of the first five Black Lynchburg city councilmen elected to office in the 1880s. In honor of this current election week, we share this story once again, but with new and important content to connect us with today. Unless otherwise noted, the excepts bordered in green are extracted from Harry S. Ferguson’s 1950 “The Participation of the Lynchburg, Virginia Negro in Politics 1865-1900,” a thesis written for his Degree of Master of Arts at the Virginia State College asserting Black activism in local government in the latter half of the 1800’s.

“The…account of the important activities of these Negro councilmen, shows that they were active in educational, religious and economic affairs and had a desire to serve the citizens of Lynchburg who placed them in office.” - Ferguson

From 1885 to 1889, Lynchburg voted its first five African Americans into City Council. At this time, “the Hill City was the largest hub of African American life and culture in Virginia west of Richmond.”1 Indeed, fifty percent of the city was Black in the middle decades of the century.

During the election years of this period, the city became a veritable hot bed of campaigning and electioneering by local Negro politicians, who fought to have their fellow citizens represented in the affairs of the local government.

Ferguson names the five councilmen and situates them in their context:

Jefferson Anderson and Henry Edwards represented the city’s third ward from 1885 to 1887, while John W. Crawford, John W Wilson, James H. Merchant, and Jefferson Anderson served the city’s first and third wards from 1887 to 1889.

These councilmen experienced political discourse not dissimilar from the malicious lashing we often hear today from political figures. An editor from the Lynchburg News wrote:

‘If you are white, stay white, for the Anglo-Saxon who forgets his race, blood, and proud heritage and bands with the Negroes deserves unspeakable score and the whip of scorpions’ (Lynchburg News, November 3, 1884).

But the African American community prevailed in electing these men to office, similar in story to other towns and cities in the South, as the Black collective voice brought strength to its people.

The campaign of 1887 for the election of the city councilman was a stormy and controversial one. . . The rift between the Negro and the white members was over representation by Negroes in all the wards.

The fact that this sweeping victory for the Negroes was distasteful to his political adversaries was but a reflection of the political potentialities of the Negro of that day, when he lined up in a concerted effort behind a purposeful movement.

These five men were businessmen, property owners, husbands, and fathers. Several grew up children of enslaved parents and they all lived through the Civil War.

(Thomas) Jefferson Anderson was born January 5, 1853, of slave parents in Amherst County. He acquired a common school education which was sufficient to operate a grocery business at Madison and Twelfth Streets.

Anderson later superintended the city’s cemetery. At some point, his children moved away seeking a better life in the North. Poet and musician T. J. Anderson III, the Great Grandson of (Thomas) Jefferson Anderson honored his Great Grandfather in a poem published at Bridge of Lament this summer.

Read the full poem at This Our Passing.

“Oh Great Grandfather, it is always here that I see you

standing between long limbed trees and bright celestial sun,

between the clouds of freedom that telegraph your dreams.”

Henry Edwards was born September 4, 1834 of slave parents at Charlotte Court House, Virginia and came to Lynchburg after the Civil War. He owned two pieces of property…After working as a laborer in a tobacco factory, he was made floor manager. Edwards was also a professional politician, a good orator…After serving on the city council, he operated a grocery store and saloon…until his death.

John W. Wilson was born in Appomattox County, Virginia, June 1841...He owned several places of property. He was a first-class carpenter and contractor and built many houses in the city of Lynchburg. His outstanding construction was the old Negro Church, the Court Street Baptist Church. . . . He was active in fraternal and civic organizations and served on the deacon board of the Court Street Baptist Church, …appointed to serve on the Public Building and Sanitary Committees.

John W. Crawford was born in 1845 of slave parents in Campbell County and was never married. He owned two lots located on Daniel’s Hill…Crawford owned and operated an antique and used bookshop on Main Street in the 700 block. He was a member of the Court Street Baptist Church, and was also connected with the leading Negro civic and fraternal organizations of his day . . . [As a councilman, he] served on the Market, Safety, Sanitary and Parks Committees”

James H. Merchant owned his home at Fourteenth and Taylor Streets. He was born of slave parents in Lynchburg, December 20th, 1842. . . Merchant was a barber by trade . . .Mr. Merchant [served as a councilman] on the Alms House, Schools, and Claims Commitee . . .

The service of these five men improved the morale of the Black community in Lynchburg and boosted their quality of life:

Record of these men in office showed that the members of their race were capable and willing to serve all the citizens of the city. It further proved to the colored citizens that office holding was as important as voting. The fact that the Negro had now reached the stage where he could have a voice in the actual operation of the city’s government seemed to have inspired a new political zeal in him for in the coming councilman’s election of 1887, he was able to elect three new councilmen and re-elect an incumbent.

The . . . account of the important activities of these Negro councilmen, shows that they were active in educational, religious and economic affairs and had a desire to serve the citizens of Lynchburg who placed them in office.

They were part of an important movement of the African American people of the city in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s.

Local Black leaders used the strength of their community to…bargain for better wages through organized labor, open a public high school, bring two colleges to Lynchburg, establish the statewide Virginia Teachers Association, and build a 2,500-person-capacity church. (The Lynchburg Musem) 2

But reactionary forces were at work, and the dawning of the twentieth century saw political power eroding from the Black community.

In the election for councilmen held May 23, 1889, the Negro Republican candidates were defeated by a narrow margin, due to the split in the Party. . . . This defeat engendered by a split in the Republican camp makes true the old Roman axion, Divisa et empera, divide and rule.

With the going out of the Negro councilman in 1889, the Negro political power also went out to remain until 1898 when a coalition of white and Negro Republicans…came on the scene to represent Daniel Butler for the United States Congress…Daniel Butler was a scholar, orator, poet, politician, and leader of his people . . . but lost the election . . .

Butler’s campaign for congress in 1898 brought a close to the political venture of the Lynchburg Negro at office holding for in the near future came the Virginia Constitution of 1902 with its new acts of voting requirements that meant the disfranchisement to most of the Negro citizens as far as local and state politics were concerned.

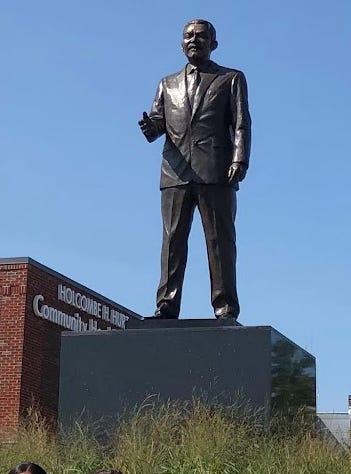

Bridge of Lament writer Jeremiah Forshey reflected this summer on Butler’s loss in that election. Forshey shared that Butler’s unsuccessful campaign came at a time when Confederate statues were going up in front of courthouses across the South, including our own here in Lynchburg, in an effort to reclaim white dominance.

[The Lynchburg Confederate statue dedication] fell right in the middle of a vicious white backlash against Black representation in local and national politics. No one would have been unaware of those facts, any more than you or I are unaware of our own day’s most heated political issues. That entire white crowd would have been aware of their immediate political context, which is: Shortly after Lynchburg’s Black councilmembers were removed, and while Virginia’s constitution was being rewritten to ensure no more Black representatives were elected, a white crowd placed a memorial to the Confederacy and its cause in the city’s most prominent location. (Day 9: The History of Lynchburg's Confederate Monument (substack.com)

Discriminatory laws were passed during the decades following Butler’s defeat in the 1898 election making him the last African American from Lynchburg to run for city, state, or federal office for nearly half a century.3 However, as Ferguson asserts, the 1880s decade was foundational in social progress for the Black citizen.

Even though their political power was short-lived, due to the innovation of certain reactionary forces, over which they had no control, they did develop a political consciousness which helped them in the future. They did benefit materially by having provided for them schools, and civil liberties . . .

The first five Black city council members laid a foundation that later generations would build upon. Today’s current African American council members, Sterling Wilder and Larry Taylor, in Lynchburg work from a strong heritage. They follow on the heels of important figures such as Treney Tweedy, Lynchburg’s first Black female mayor in 2018, M.W. Thornhill Jr, Lynchburg’s first elected Black male mayor in 1990, and Carl Hutcherson Jr. who served as mayor between Thornhill and Tweedy.

Thornhill was active in politics beginning in the 1960s when he first ran for Council, and he served throughout his life both with the NAACP and Lynchburg Voters League. Retired Councilman Carl Hutcherson Jr told the Lynchburg News Advance, “[Thornhill] put his business on the line for civil rights, and he put his life on the line for civil rights and he made a tremendous impact across Central Virginia and the state,”.4 Thornhill was a member of the Court Street Baptist church that John W. Wilson, of the first five Black councilmen, built, and which served as a meeting place for the African American community throughout the civil rights period.

The modern era provides rich examples of Black public servants in Lynchburg. They share a legacy with the city council that began immediately after the Civil War when Lynchburg voted in the first five African American councilmen. Ferguson explains these early years gave the community the “political consciousness” it knows today.

This week when you vote, vote knowing that you stand on the sacred ground of African Americans who made, and continue to make, a better city through hard work, sacrifice, and commitment to its wellbeing.

Daniel Butler - Old City Cemetery (gravegarden.org)