Day 15: Hope from the Ashes: The Rise of Lynchburg’s Black Colleges (Part Two)

by Jeremiah Forshey

Yesterday, we looked at some of the challenges facing the Black community in Lynchburg in the 1880s: violent white backlash, unjust policing, unequal school funding, how a history of racist laws made it difficult to find qualified teachers, and the threats of extremist violence against Black schools and teachers. We looked at some of the opportunities and victories, too: a political coalition that secured state-wide free public schooling, and most importantly, the way Black churches stepped up to provide for the educational needs of the community.

Toni Morrison has said, “The history of African Americans that narrows or dismisses religion in both their collective and individual life … is more than incomplete—it may be fraudulent.”1

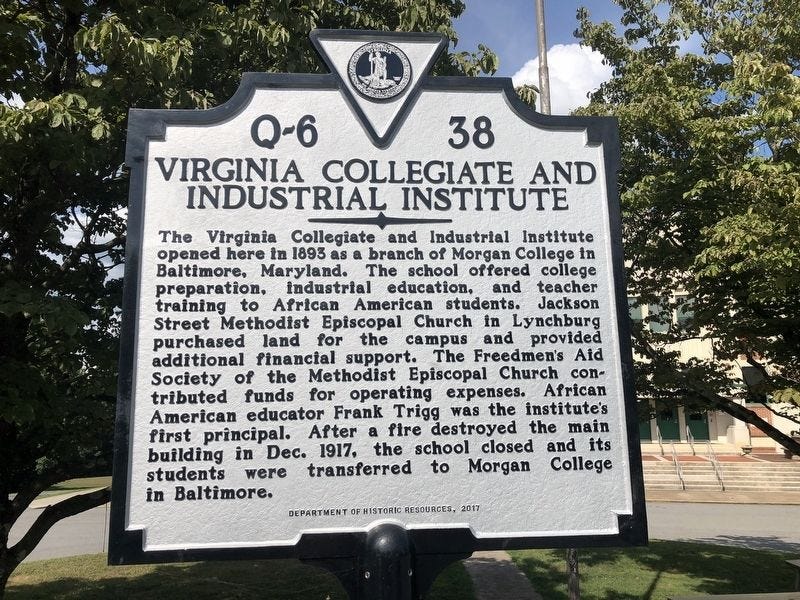

Her insight is fully borne out in the history of Black education in Lynchburg. In 1886, Court Street Baptist Church was instrumental in founding Lynchburg’s oldest college: the institution now known as Virginia University of Lynchburg (VUL).2 Seven years later, in 1893, Jackson Street Methodist Church was “the singular driving force”3 behind the creation of another: Virginia Collegiate and Industrial Institute (VCII).

I feel the need to pause before I even begin. It is a deep and unfortunate irony that even though Lynchburg is known as a college town, the oldest college in our city is one that most people know little about. Even many Lynchburg residents don’t know it’s here. This is really unfortunate, because the institution’s history is an incredible profile in courage, vision, and pure grit.

It also gives us an important window into our racial history as a town and nation. To see that better, we need to understand what was one of the most urgent and critical debates in the Black intellectual community at the turn of the 20th century: Booker T. Washington or W. E. B. Du Bois?

Two Views on Education

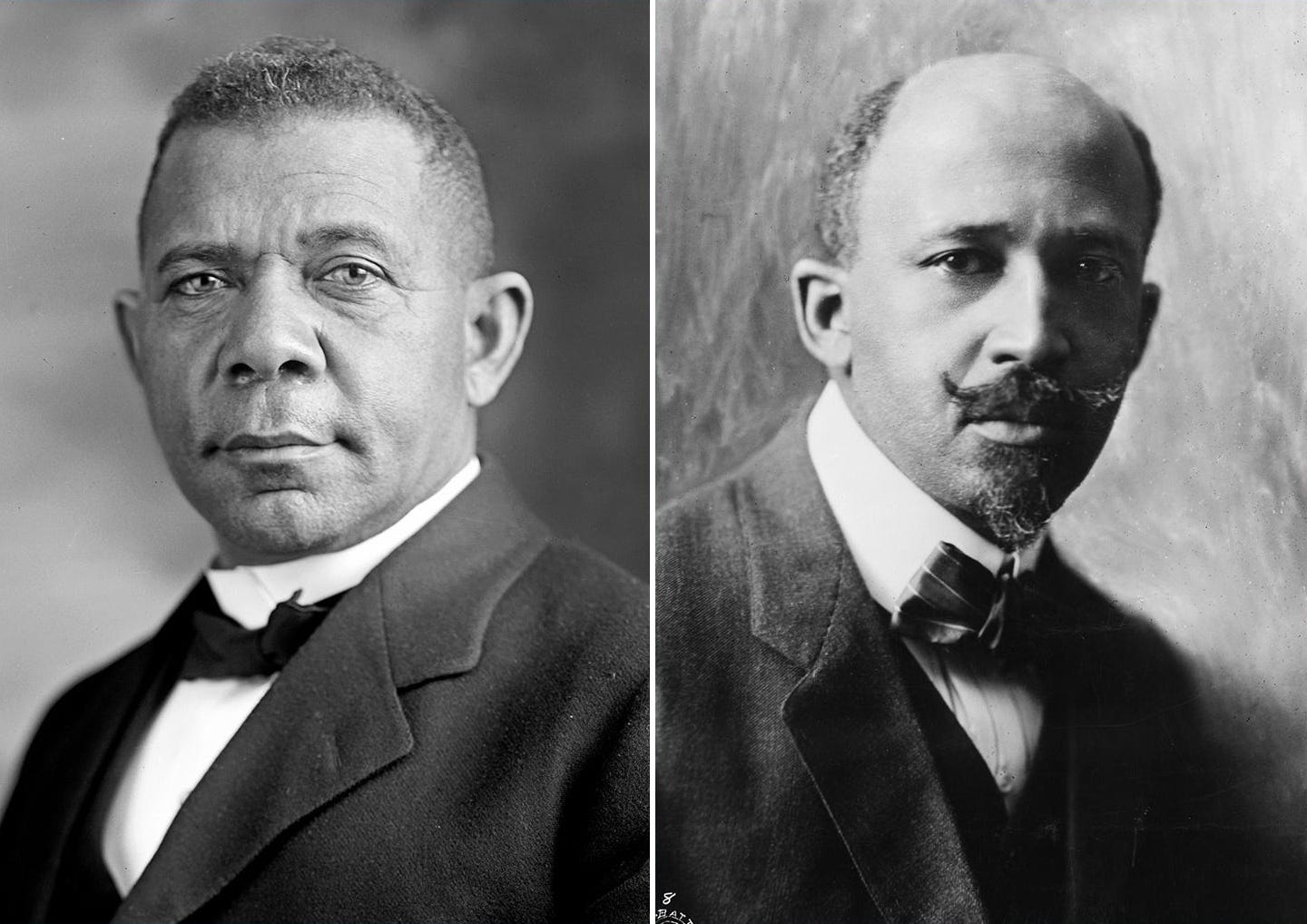

The question was, who had the better vision for what was called at the time “racial uplift”—the process of improving the condition of Black Americans in a society that allowed them freedom but not equality, and no restitution for 300 years of plunder.

Washington’s view was that what Black Americans needed most was economic opportunity. He founded the Tuskegee Institute and supported a network of “industrial institutes” (trade schools) that taught reading, math, manners, and trades. Students and teachers worked in trade shops on the grounds to help fund the schools. Washington stressed the dignity of manual labor and was suspicious of a liberal arts education that did not focus on job skills.

To ply those trades and secure that economic opportunity, Washington believed that Black Americans needed to cooperate with their white neighbors, and this meant not offending them. In his most famous speech, given in 1895 at a trade convention in Atlanta, Washington proposed “the Atlanta Compromise.” He argued that Black Americans should stop pushing for civil rights and social equality and focus instead on being economically useful, and let rights and equality come eventually. He asked white business leaders to hire and trade with Black Americans, promising they would be “patient, faithful, law-abiding, and unresentful.”

White business interests loved this message and gave it thunderous applause—at the convention, in the press, and with donation money to Washington’s schools. But it did not sit well with many in the Black community. Some felt that Washington failed to stand up for Black equality and accommodated racist notions popular among whites that Black Americans were well-suited for labor but not ready for leadership or participation in democracy.4

W. E. B. Du Bois was among those critics. He rejected the view that honest labor would eventually deliver rights and equality:

“Two hundred and fifty years the black serf toiled at the plow and yet that toiling was in vain… [T]wo hundred and fifty years more the half-free serf of today may toil at his plow, but unless he have political rights and righteously guarded civic status, he will still remain the poverty-stricken and ignorant plaything of rascals.”5

This line of talk was much less popular with white audiences.

Du Bois zealously defended the importance of liberal arts education for the Black community. At the turn of the 20th century, liberal arts education meant studying Greek and Latin language and literature, advanced mathematics, history, music, and philosophy. It was the education afforded to white students at elite American universities. Du Bois argued, “that Higher Education which must underlie true life” was not just about teaching people how to work and make money, but about inculcating “intelligence, broad sympathy, knowledge of the world that was and is, and of the relation of [human beings] to it.”6 He rejected the view that Black students just needed job skills and couldn’t or didn’t need to learn those things.

Taking a system-wide view of education, Du Bois acknowledged that job training was broadly important, and not everyone needed a liberal arts education, but some people did. Those people would be leaders in their community--teachers, scholars, pastors, and politicians--and help elevate everyone else. To train up those cultural leaders, Du Bois insisted that the first priority was Black liberal arts colleges, “providing for the higher training of the very best teachers.”7

Two Black Colleges in Lynchburg

Lynchburg’s two colleges were founded on these two different philosophies of Black education, and they came in the order Du Bois suggested: VUL was founded first as a seminary and liberal arts school in 1886; VCII followed as an industrial institute in 1893.

In 1893, Frank Trigg and the Jackson Street Methodist Church founded Virginia Collegiate and Industrial Institute (VCII). The campus was down the hill from VUL, in the same spot that William Marvin Bass Elementary School now sits.

Trigg was a classmate of Booker T. Washington’s, and VCII was modeled on his Tuskegee Institute. The school was called “Collegiate and Industrial” because there was also a track for students who wanted to continue on to Morgan College, a teacher prep school in Maryland. But even those collegiate students were being prepared specifically as teachers in rural schools, so they also learned basic trade skills (such as gardening and sewing) that would help them thrive in rural communities. Like at Tuskegee, all VCII students did manual labor on campus as part of their education.8

Whatever our view on the disagreement between Washington and Du Bois, we must recognize the important contributions VCII made. The historian Nancy Elizabeth Fitch, who in her storied career taught at both University of Lynchburg and Randolph College, wrote, “For the freedmen, both sides of the curricular divide were important to improvement in the lives and futures of persons of African descent.”9

VCII burned down on December 10, 1917, during the Christmas holiday, and the school closed. It is unknown how the fire started.

Virginia University of Lynchburg

Immediately at the end of the Civil War, Black Baptists in Virginia began organizing to build seminaries and teacher training schools. They reached out several times to white Baptist associations for help. The earliest request, in 1868, was rudely denied, in openly racist terms.10 A second request was heard at the 1883 Congress of Virginia Baptists, held here in Lynchburg. In response, two white Baptist ministers gave speeches from the floor filled with racist invective. The second minister succinctly articulated the white supremacist attitude that was shamefully common at the time: “the Negro…ought to be trained for the place for which God endowed him. He cannot be a judge, a professor in a college, a legislator; he can be a laborer, a teamster, a stevedore....God never intended all men to be alike.”11

In that response, we see why Washington’s program was so favored by the white establishment. It accomplished good and necessary things, but at the cost of refusing to challenge white supremacy. It shows why Du Bois’s response was so necessary.

Virginia Black Baptists hoped for a better reception from their white brothers and sisters in the North. They reached out to the American Baptist Home Mission Society (ABHMS), who were spending considerable money founding schools for Black students in the South. There they encountered a different problem: white paternalism. The ABHMS was willing to give money for a new school, but the money came with strings attached. The new school would have to use the curriculum ABHMS selected, built around the view that Black people did not need a liberal arts education, and the school would have to be controlled by a white board.

The Virginia Black Baptists rejected the offer. They wanted a school owned and controlled by their own members. So they chose Philip Fisher Morris, pastor of Lynchburg’s Court Street Baptist Church, as president for their new school. Morris had stated his view: “He who would be free must himself strike the blow.…If we as a race are ever to be educated in the true sense, we must be educators.”12

They also chose Lynchburg as the location for the new school, as it had several advantages. The committee’s report noted that Lynchburg “offered the greatest bonus—accessibility, centrality, and salubrity [a healthy environment],” and they had located an available site that offered “six [acres] of beautiful table land.” But perhaps the greatest benefit was that by the late 1880s, Lynchburg was a majority Black city.13 As we discussed in yesterday’s post, tobacco and railroad jobs had brought in many Black families. This made it easier to secure housing for students and provided “a sense of ‘social comfort.’”14 As the Lynchburg Museum says, “the Hill City was the largest hub of African American life and culture in Virginia west of Richmond.”

The white Northern Baptists (the ABHMS) were skeptical. Their superintendent of education said, “it will be a hundred years before a Negro will be competent to be president of a college.”15 The project continued anyway. Morris broke ground, built the first building, secured funding (including donations of his own money), and VUL opened its doors to the first class in 1890, under the name Virginia Seminary.

Without access to resources controlled by the white Baptists, the school faced unrelenting financial pressures. These forced Morris into a limited agreement with the ABHMS: some money for some oversight. Curriculum, control, and hiring authority remained with the Black Baptists, but ABHMS insisted on the authority to conduct annual inspections and fire any teacher they thought was subpar. That agreement brought in necessary funds, but cost Morris his presidency. Facing discontent with the agreement and the difficulties of maintaining two demanding jobs (pastor of Court Street Baptist and college president), Morris resigned.

The second president, and the first professional academic devoted full-time to the presidency, was Gregory W. Hayes. Hayes was a brilliant polymath, a firebrand, and dedicated champion of the full and uncompromising equality of Black people. The story of how he came to the notice of the VUL board is a profile in principled courage.

Before serving as VUL’s second president, Gregory Hayes was a history and mathematics professor at a Black college in Petersburg, Virginia. In one of his history classes, he told his students:

“This history you study is supposed to be the history of the United States. It is incorrect. It does not include the records of the Black man. If a true history of the United States is ever written, a history that will include the records of the Black man, a Negro will have to write it.”16

An account of that conversation got back to Gov. McKinney of Virginia. The governor darkly commented to the college president that Hayes was “a dangerous Negro,” and the president must get rid of him. The president did not, at least not immediately. But when Gov. McKinney came to give the commencement address at the Petersburg school, he told the assembled graduates that they should not complain about their treatment, but should be thankful that “the white man” had brought them from Africa to America and “civilized” them.17

Hayes stood up from his chair on the platform, walked over to the college president, and set down the basket of diplomas he had been holding. He said, “If that is education, I do not want it,” and stormed off the platform.

That protest cost Hayes his job at Petersburg, but the representatives from Lynchburg in the congregation “sensed immediately that this gentleman would be an excellent person both as to preparation and as to attitude for heading the new school.”18 Hayes was elected as VUL’s second president in September 1891.

Hayes leaned into his new duties with vigor. He undertook building projects, sought out highly qualified faculty, and sharpened the curriculum, instituting a rigorous liberal arts course of study with three tracks: Preparatory (remedial work), Normal (teacher training), and Academic (full liberal arts degree). The Academic students were studying the same advanced courses that students at Harvard and Yale studied: Music, Trigonometry, History, Ethics, Philosophy, Economy, International law, German, French, and Greek and Latin language and authors. By the start of his third year as president (1893), VUL had over 300 students.

Even more importantly, in the words of Dr. Ralph Reavis:

“The school at Lynchburg quickly came to represent more than a means of filling educational needs not otherwise provided. It came to represent a symbol of the principle that Virginia’s Negro Baptists should own and control their own school. It became a repository of the principles of self-reliance, race pride, ancestral reverence, faith in each other, and confidence in Negro leadership, which Morris had said were essential elements of the Negro educational experience.”19

Inspiration for Today

I see in VUL inspiration for our own time. The same groups and social forces behind the first “Massive Resistance” are again pressuring the nation to keep Black people out of schools (this time by removing Black authors), to run all curriculum past white boards for approval (under the guise of removing “woke indoctrination”—this effort is happening right now in Lynchburg), and to submit to the white agenda or lose funds. We witnessed this over the weekend in Charlottesville. The Trump administration threatened to withhold federal funds from the University of Virginia if its president James Ryan did not resign. They said he was not doing enough to remove diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility initiatives. Rather than risk the University’s funds, Ryan resigned.

The heroic and hard-won legacy of Virginia University of Lynchburg is right here in our own city. The school has had famous alumni, like the poet Anne Spencer, and presidents, like Civil Rights icon Vernon Johns. Many of our city’s beloved Black teachers, whom Beatrice Hunter remembered a few days ago, came through VUL. It has had outsized academic successes: In 2024 Forbes magazine ranked its online doctorate in healthcare administration #1 in the nation. This is an institution that more Lynchburgers should know about, celebrate, and support.

I do not want to paint an overly rosy picture. VUL, like any institution, has struggled for money its entire existence. And more than most institutions, this struggle is in its DNA. As one local Black scholar observed, VUL carries a “Hayes legacy” as an institution devoted to Black autonomy in higher education, and that legacy comes at a high financial price.20

But that legacy of struggle itself is an inspiration. Overcoming the violent racism of their neighbors and rejecting the patronizing racism of their supposed allies, VUL rose as a testament to what one historian has called “one of the most moving chapters in American social history”21: the immediate and vigorous efforts of formerly enslaved men and women to secure the blessings of education for themselves and their children.

Jeremiah Forshey is a writer, former English teacher, and resident of Lynchburg. He and his wife Elisa have three children.

Morrison, Toni, “God’s Language.” The Source of Self Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations. Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

Like many schools, VUL has undergone several name changes in its history: Lynchburg Baptist Seminary in its planning stages, then Virginia Seminary when it opened its doors, then Virginia Theological Seminary and College, Virginia Seminary and College, finally changing to VUL in 1996. Those names will appear in historical sources, but for the sake of readability I’ll refer to the institution uniformly as VUL.

Nancy Elizabeth Fitch, “For God and the Race—Virginia Collegiate and Industrial Institute, ‘In the Valley of Virginia’—an Introduction.” Unpublished manuscript available at the Jones Memorial Library in Lynchburg.

For example, Kelly Miller, dean of Howard University, drily observed that Washington “is a diplomat, and a great one. He sinks into sphinxlike silence when demands of the situation seem to require emphatic utterance … The white race saddles its own notions and feelings upon him, and yet he opens not his mouth.” (qtd. in Ralph Reavis, Virginia Union University, Virginia University of Lynchburg: Two Paths to Freedom. African American Publishers of Virginia, Richmond: 2000. Page 129.)

W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth.”

Ibid.

Ibid.

This information taken from the unpublished papers of Nancy Elizabeth Fitch. For any aspiring young historian out there, not much is known about VCII, and Dr. Fitch’s research might be the furthest anyone has gone. Her unpublished manuscripts are in the Jones Memorial Library.

Nancy Elizabeth Fitch, “For God and the Race—Virginia Collegiate and Industrial Institute, ‘In the Valley of Virginia’—an Introduction.” Unpublished.

Ralph Reavis, Two Paths to Freedom. This account of VUL’s founding is deeply indebted to Dr. Reavis’s book.

Qtd. in Reavis, page 33.

Qtd. in Reavis, page 44.

Reavis, page 44.

Ibid.

Ibid, page 60.

Ibid, page 65.

Qtd. in Reavis, page 66.

Ibid, page 65.

Ibid, page 47.

Lois Gochu, “Evolution of Black Education in Virginia: Virginia Seminary’s Equivocal Role.” Lynch’s Ferry, Fall 1990, vol. 3, no. 2, pages 10-13.

Eugene Genovese, qtd. in Reeves, page 2.

Thank you for this important history lesson.