Day 14: Hope from the Ashes: The Rise of Lynchburg’s Black Colleges (Part One)

by Jeremiah Forshey

The posts for the next two days are arranged to fit our bridge metaphor--to move from lament to hope. I have a hopeful story to tell. But to properly appreciate its triumph, I need to begin in difficult times. Tomorrow I will tell the story of the founding and early days of Lynchburg’s oldest institution of higher learning: the Virginia University of Lynchburg. Today I need to explain the context of the time it was founded.

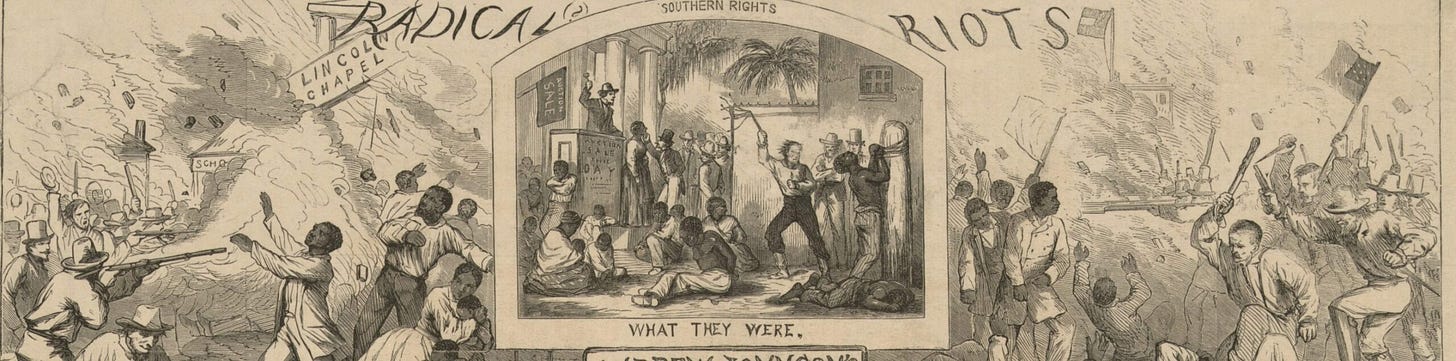

Immediately after the Civil War, white racial violence against Black residents exploded in Lynchburg, as it did across the South. To understand why, we have to understand what W. E. B. Du Bois meant by “the psychological wages of whiteness.” Du Bois points out that even whites too poor to “own”1 a slave benefited from the system of slavery because it conferred social status and privileges. No matter how poor and lowly a white man might be, he was at least not the bottom rung of the social ladder. This wasn’t a mere feeling. It was a kind of privilege that people still pay good money for: to have others owe you public deference, to be allowed in spaces others can’t go.

Now that Black people could walk free in the same places as their white neighbors, many white Southerners felt that their status and privileges had been taken away. They felt robbed of “the psychological wage of whiteness.” And if a Black man did not tip his hat and stand out of the way on the sidewalk, a resentful white man might feel it as a personal affront and seek to “defend his honor,” a common justification for violence in the 19th century South. This is what the editor of the Lynchburg News meant when he wrote in 1866, “They have got to be stopped, or there will be no such thing as living with them. … [They are] insulting and trampling upon white men at their pleasure.”2

Racist assaults happened in Lynchburg streets, businesses, and drinking halls immediately after the war.3 It got so bad that when a local entertainment hall invited a speaker to lecture on “the virtues of dueling,” federal agents from the Freedman’s Bureau shut down the event. One agent said that most white Lynchburgers already believed they had a “private right…to shoot, assault, and harass Yankees and blacks” in the name of “Southern chivalry.”4

Racial violence wasn’t just personal. It was also legal. The war ended in 1865, and in 1866, Lynchburg created its police department. Sadly, justice was not blind. John Averitt, a Black Republican leader, told the 1869 House Select Committee on Reconstruction that any Black men who “get arrested … don’t stand much chance of being cleared.” A white resident told the same committee that Black Lynchburgers were “practically denied the protection of the laws. [They were regularly] tried for small offences, and sentenced to the Penitentiary for long terms, and in many instances, upon slight testimony.” John Boisseau, then chairman of the Lynchburg City Council, said he did not “know of an instance where the … colored man has been shot down or murdered” and the law would “bring the offending party to justice, but in every instance I know of the offending party has escaped justice.”5

Ironically, racism contained the seeds of its own undoing. As Lynchburg’s post-war economy adjusted to the end of enslaved labor, more tobacco laborers and railway workers were needed. These were among the jobs that Black men were allowed to work, and families flocked to the city. White and Black laborers worked side by side in these jobs, and many found that their interests aligned. In the 1870s and 1880s, working class whites and Blacks organized together across the state of Virginia, pushing forward reforms that benefitted them both. One effect of this cooperation was something we wrote about in our first bridge crossing: from 1885 - 1889, Lynchburg had five years of equal representation, electing five Black men to City Council and nominating a Black man as our Congressional representative.

Another effect of this multiracial coalition was a state public school system that offered free education to all children regardless of race. Lynchburg’s Samuel Kelso was a driving force behind this state-wide initiative. Born into slavery, Kelso rose to be the delegate for Lynchburg and Campbell County to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1867–1868, defeating a white conservative candidate and becoming the first Black Lynchburger elected to public office. He succeeded in getting the public school resolution passed, over strenuous objection that rich white families shouldn’t have to pay to educate other people’s children.

Unfortunately, Kelso and the other Black delegates were overruled when they tried to insist that the schools should not be segregated. They knew “it was unlikely that the separate black schools would receive the same benefits as the white schools.”6 The resolution caved to racist concerns and overwhelmingly voted that white and Black students would not be taught in the same buildings. Beatrice Hunter has discussed Kelso’s role in setting up schools in Lynchburg for Black children. He returned from the convention to teach in Lynchburg.

Especially without equal resources for Black public schools, there was a critical need for teacher training colleges (called at the time “Normal schools” or “Normal institutes”) for Black young adults. Some white Northerners came south to teach (see, for example, Beatrice Hunter’s piece on Pennsylvania native Jacob Yoder), but Black community leaders saw the benefit of having authority figures and role models in children’s lives that looked like them and understood them.

But finding qualified Black teachers at the time was not easy. From 1819 to 1865, it had been illegal in Virginia to teach Black people to read. Despite heroic efforts to teach and learn that risked twenty lashes if caught, the literacy rate and level of education among Black adults in 1870 was understandably low. As one pastor and educator said, “The lack of [education] in us as a race is the legitimate effect of our former condition of 245 years.”7

Limited funds and lack of teachers were not the schools’ only problems. Racist violence remained an ever-present threat. The KKK, formed in 1866, burned Black schools and threatened and beat their teachers. One teacher at a Virginia freedman’s school recounted in 1868, “The Ku Klux have been in our neighborhood, and we have received notice that they intend giving us a call … Their outrages and murders have become matters of history; one of the missionaries in this part of Va.—a New England man, a cripple, was dragged from his bed and over the ground to the woods and terribly beaten. The poor wife never left him, and took him back nearly dead.”8

The need for Black teacher training schools was keenly felt. Similar to the story Rebecca Pickard told, the Black church stepped in to fill the gaps. In the face of pervasive white supremacy, racist violence both legal and extralegal, and massive systemic inequalities, Black churches in Lynchburg came together to provide for the education of their people. We’ll read more about that tomorrow as we examine the birth of the school known today as Virginia University of Lynchburg.

Jeremiah Forshey is a writer, former English teacher, and resident of Lynchburg. He and his wife Elisa have three children.

I put “own” in quotes because I categorically deny that a human being can actually be owned by another. We are not property. The unjust laws of a community convinced some people that they had a right to “own” their neighbors, the way they owned things or animals. But the enslaver never “owned” a single slave with any more legitimacy than a kidnapper or child abductor today “owns” his victims.

J. G. Perry, quoted in Steven Elliot Tripp, Yankee Town, Southern City: Race and Class Relations in Civil War Lynchburg, 1997, page 225.

See Steven Elliot Tripp’s Yankee Town, Southern City: Race and Class Relations in Civil War Lynchburg for several examples. It is available at Given’s Books.

Tripp, page 227.

The examples in this paragraph are taken from Tripp, page 236.

Lois Gochu, “Evolution of Black Education in Virginia: Virginia Seminary’s Equivocal Role.” Lynch’s Ferry Fall 1990, vol. 3, no. 2, pages 10-13.

Philip F. Morris, qtd in Ralph Reavis, Virginia Union University, Virginia University of Lynchburg: Two Paths to Freedom. African American Publishers of Virginia, Richmond: 2000. Page 45.